Vrints C, Andreotti F, Koskinas KC, et al. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the management of chronic coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. 2024;45(36):3415-3537. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehae177

Virani SS, Newby LK, Arnold SV, et al. 2023 AHA/ACC/ACCP/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline for the Management of Patients With Chronic Coronary Disease: A Report of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2023;148(9):e9-e119. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000001168

Byrne RA, Fremes S, Capodanno D, et al. 2022 Joint ESC/EACTS review of the 2018 guideline recommendations on the revascularization of left main coronary artery disease in patients at low surgical risk and anatomy suitable for PCI or CABG. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2023;64(2):ezad286. doi:10.1093/ejcts/ezad286

Gragnano F, Cao D, Pirondini L, et al. P2Y12 Inhibitor or Aspirin Monotherapy for Secondary Prevention of Coronary Events. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2023;82(2):89-105. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2023.04.051

Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2019;140(11):e596-e646. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000678

Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, et al. Fourth Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction (2018). Circulation. 2018;138(20):e618-e651. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000617

Moss AJ, Williams MC, Newby DE, Nicol ED. The Updated NICE Guidelines: Cardiac CT as the First-Line Test for Coronary Artery Disease. Curr Cardiovasc Imaging Rep. 2017;10(5):15. doi: 10.1007/s12410-017-9412-6. Epub 2017 Mar 27. Review. PubMed PMID: 28446943; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5368205.

This chapter addresses symptomatic stable coronary artery disease (CAD).

Definition, Etiology, PathogenesisTop

Angina pectoris is a clinical syndrome characterized by chest pain (or its equivalent) due to myocardial ischemia, usually developing on exertion or caused by stress and not associated with necrosis of cardiomyocytes. In some patients the pain may be spontaneous. Angina reflects an inadequate oxygen supply in relation to myocardial demand. Stable angina pectoris is diagnosed in patients with symptoms of angina and no worsening over the prior 2 months.

Etiology and pathogenesis: see Ischemic Heart Disease.

Clinical Features and Natural HistoryTop

1. Symptoms: The clinical diagnosis of angina is based on history. A detailed characterization of the symptom complex is critical to the patient assessment.

Anginal chest pain is typically retrosternal in location and may radiate to the neck, jaw, left shoulder, and/or left arm (and usually further along the ulnar nerve to the wrist and fingers), to the epigastrium, or rarely to the interscapular region. Pain is caused by exertion (threshold may vary from patient to patient) and emotional stress. It usually lasts a few minutes and is relieved by rest or sometimes decreases in the course of continued exercise. Pain is frequently more severe in the morning and may be exacerbated by cold air or a heavy meal. Pain intensity is not related to body position or phase of the respiratory cycle. It usually resolves within 1 to 3 minutes of sublingual administration of nitroglycerin (if it resolves after 5-10 minutes, it is probably not related to myocardial ischemia and may be caused, eg, by esophageal disease). Pain may be absent in patients with an anginal “equivalent,” particularly exertional dyspnea; however, it may be challenging to distinguish the anginal equivalent from a pulmonary cause.

Typical angina:

1) Is substernal and referred in a typical way.

2) Is caused by exertion or emotional stress.

3) Resolves at rest or after sublingual administration of a nitrate.

Atypical angina fulfills 2 of these criteria. Nonanginal pain meets only 1 criterion.

2. Grading of angina based on its severity (Table 3.11-9): Grading the severity of angina is helpful in monitoring the course of symptoms and provides a basis for therapeutic decisions. In a significant proportion of patients symptoms of angina remain stable for many years. Long-term spontaneous remissions may occur (these are sometimes only apparent and related to reduction of physical activity).

3. Signs: No signs are specific for angina. Signs of atherosclerosis of other arteries (eg, carotid bruit, ankle-brachial index [ABI] <0.9 or >1.15) increase the risk of coronary artery disease.

DiagnosisTop

1. Laboratory tests may reveal risk factors for atherosclerosis and disorders that may trigger angina. Baseline tests in a patient with stable coronary disease include:

1) Fasting lipid profile (nonfasting or fasting total cholesterol [TC], low-density lipoprotein cholesterol [LDL-C], high-density lipoprotein cholesterol [HDL-C], and triglycerides [TG]).

2) Fasting blood glucose and glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) (and oral glucose tolerance test, when indicated [see Diabetes Mellitus]).

3) Complete blood count (CBC).

4) Serum creatinine level and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR).

Moreover in patients with clinical indications perform:

1) Measurement of cardiac troponin levels (in the case of suspected acute coronary syndrome).

2) Thyroid function tests.

3) Liver function tests (after starting statin therapy).

4) Measurement of creatine kinase levels (in patients with features of myopathy).

5) B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP)/N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) (in the case of suspected heart failure).

2. Resting electrocardiography (ECG) should be performed in every patient with suspected angina. Although the results are normal in the majority of patients, some patients may have significant Q waves, indicating prior myocardial infarction (MI) (even in the absence of a clinical history suggestive of prior MI) or ECG features of myocardial ischemia, mainly ST-segment depression or T-wave inversion.

3. Resting echocardiography is indicated in all patients to detect other diseases that may cause angina, assess impaired myocardial contractility and diastolic function, and measure left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), which is necessary for risk stratification.

4. ECG Holter monitoring rarely provides significant diagnostic information and therefore should not be performed routinely. It can be considered in the case of suspected arrhythmia or vasospastic angina (Prinzmetal variant angina).

Noninvasive Imaging Diagnostic Tests for CAD

The choice of diagnostic tests depends on the clinical probability of CAD. The probability can be estimated by considering the age and sex of the patient and the nature of discomfort. Clinically useful classification is divided into a very low (<5%), low (5%-15%), and high (>15%) probability (Table 3.11-10).

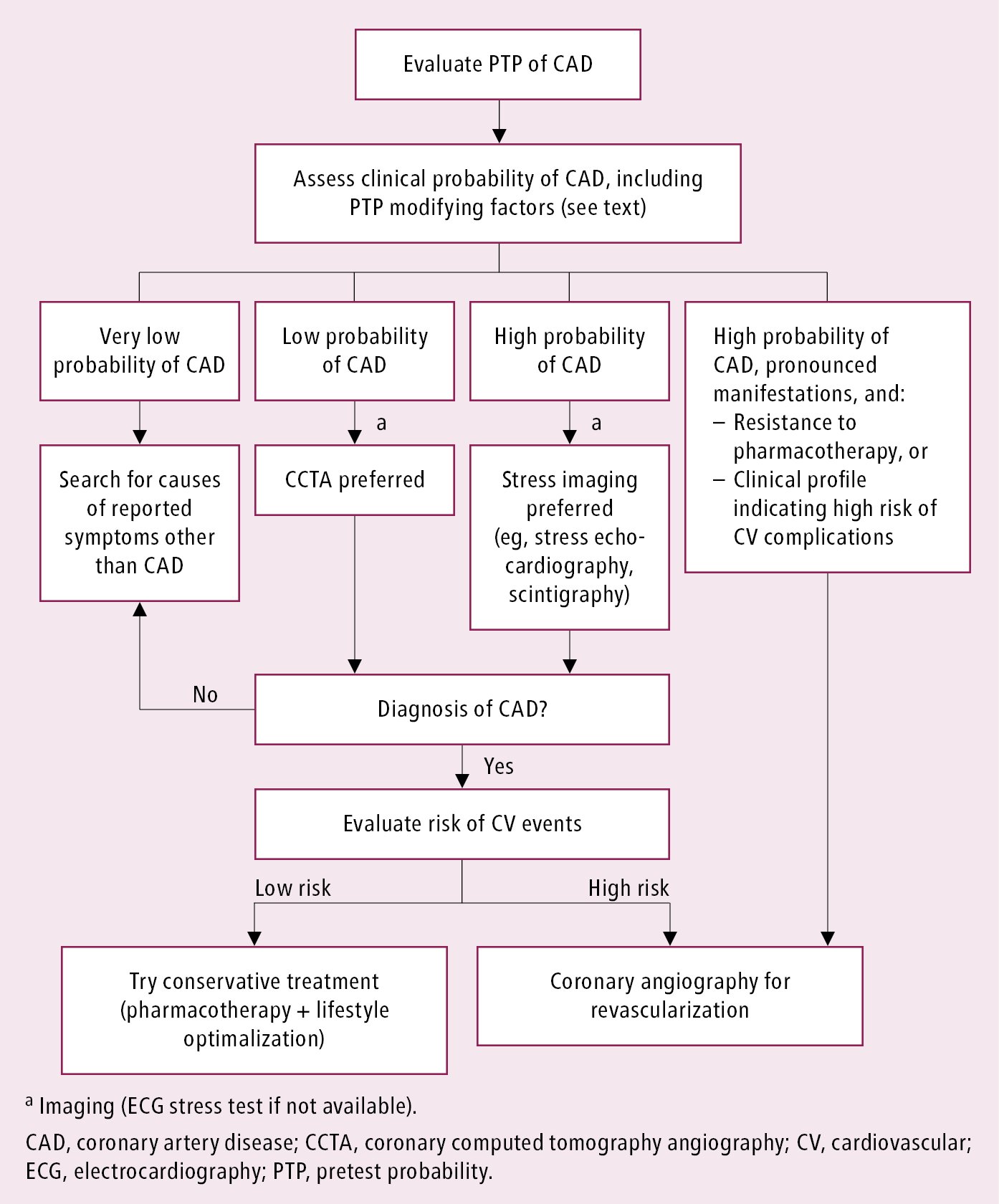

In patients with high pretest probability (PTP), noninvasive testing is performed to assess the risk of cardiovascular events. However, invasive coronary angiography may be an alternative in many such patients (see below). In patients with very low PTP, search for other causes should be considered, and noninvasive testing has limited usefulness. In patients with neither very low nor high PTP, noninvasive testing should be performed to confirm the diagnosis and assess prognosis. There are several noninvasive strategies commonly used in practice (Figure 3.11-3).

1. ECG stress testing is not recommended as a first-line diagnostic test but can be considered if noninvasive imaging testing is unavailable. It is also used to assess event risk, exercise tolerance, and symptom severity. The study is of limited diagnostic value in patients with baseline ECG features that make it impossible to interpret the recordings during exercise (left bundle branch block [LBBB], preexcitation syndromes, pacemaker rhythms).

2. ECG stress testing with imaging: The addition of imaging to stress testing improves sensitivity, specificity, and prognostic information. Stress imaging is especially useful in assessing patients who have uninterpretable ECG. The two common types of imaging are single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) with sestamibi or thallium isotopes and stress echocardiography. Imaging can be performed with pharmacologic stress (dipyridamole [trade name Persantine] or dobutamine) in individuals who are not able to exercise. However, exercise is always preferred whenever possible for the additional prognostic information that it provides.

3. Coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA) should be considered as an initial diagnostic test for those with low or intermediate probability of CAD or as an alternative to stress testing with imaging and in patients in whom stress testing yields equivocal results or is not feasible (due to limited exercise capacity or uninterpretable ECG). CCTA has a very high negative predictive value, which allows for the exclusion of CAD in lower-risk patients. Specificity and diagnostic accuracy are reduced in the setting of extensive coronary calcification and fast or irregular heart rates.

4. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and positron emission tomography (PET) are emerging modalities for cardiac imaging. They have value for the assessment of myocardial viability and ventricular function, but they are not widely used as stress testing modalities.

In patients with suspected CAD requiring noninvasive testing, clinical outcomes were similar when an initial strategy with stress testing or CCTA was compared.Evidence 1Strong recommendation (benefits clearly outweigh downsides; right action for all or almost all patients). High Quality of Evidence (high confidence that we know true effects of intervention). Douglas PS, Hoffmann U, Patel MR, et al; PROMISE Investigators. Outcomes of anatomical versus functional testing for coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2015 Apr 2;372(14):1291-300. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1415516. Epub 2015 Mar 14. PubMed PMID: 25773919; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4473773. SCOT-HEART investigators. CT coronary angiography in patients with suspected angina due to coronary heart disease (SCOT-HEART): an open-label, parallel-group, multicentre trial. Lancet. 2015 Jun 13;385(9985):2383-91. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60291-4. Epub 2015 Mar 15. Erratum in: Lancet. 2015 Jun 13;385(9985):2354. PubMed PMID: 25788230. SCOT-HEART Investigators, Newby DE, Adamson PD, Berry C, et al. Coronary CT Angiography and 5-Year Risk of Myocardial Infarction. N Engl J Med. 2018 Sep 6;379(10):924-933. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1805971. Epub 2018 Aug 25. PubMed PMID: 30145934. Moss AJ, Williams MC, Newby DE, Nicol ED. The Updated NICE Guidelines: Cardiac CT as the First-Line Test for Coronary Artery Disease. Curr Cardiovasc Imaging Rep. 2017;10(5):15. doi: 10.1007/s12410-017-9412-6. Epub 2017 Mar 27. Review. PubMed PMID: 28446943; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5368205. However, when CCTA was used in addition to stress testing compared with stress testing alone, the use of CCTA was associated with lower rates of death and MI as well as increased diagnostic certainty and performance of fewer invasive angiographies without subsequent revascularization. The radiation dose with CCTA is lower than with nuclear imaging but higher than with stress echocardiography or stress ECG, where no radiation is administered. Although either stress testing or CCTA are usually recommended in patients requiring noninvasive testing, recent national guidelines from the United Kingdom recommend a strategy of CCTA first in eligible patients.Evidence 2Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to indirectness. Kelion AD, Nicol ED. The rationale for the primacy of coronary CT angiography in the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guideline (CG95) for the investigation of chest pain of recent onset. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2018 Nov - Dec;12(6):516-522. doi: 10.1016/j.jcct.2018.09.001. Epub 2018 Sep 11. Review. PubMed PMID: 30269897.

5. Coronary angiography is the gold standard for demonstrating coronary anatomy, establishing prognosis, and assessing the feasibility of invasive treatment. Coronary angiography should be considered for the diagnosis of CAD in the following situations:

1) High PTP of CAD in patients with severe symptoms or clinical features suggestive of high risk of cardiovascular events. In such cases it is justified to proceed to early coronary angiography without prior noninvasive imaging with the intention of revascularization.

2) Coexistence of typical angina and systolic left ventricular (LV) dysfunction (LVEF <50%).

3) Equivocal diagnosis made on the basis of noninvasive tests or conflicting results of various noninvasive tests (this is an indication for coronary angiography with measurement of functional flow reserve [FFR], if necessary).

4) Unavailability of imaging stress testing, special legal requirements associated with certain professions (eg, aircraft pilots).

Risk Stratification Based on Clinical Data and Noninvasive Imaging

Estimating the subsequent risk of cardiovascular events uses data from the clinical evaluation, ventricular function, and results of stress testing or CCTA. Markers of increased risk:

1) Clinical: Increased age, history of diabetes mellitus (DM), current smoker status, hypertension, elevated cholesterol, peripheral vascular disease, and chronic kidney disease (CKD). Evidence of clinical heart failure and ECG abnormalities are additional risk markers.

2) LV function: Ventricular function is the strongest long-term predictor of survival. An LVEF <50% indicates elevated risk; the risk continues to increase with a lower LVEF.

3) Noninvasive tests for ischemia: High-risk findings include >10% area of ischemia on SPECT or >3 dysfunctional segments on stress echocardiography. Intermediate-risk findings include area of ischemia of 1% to 10% on SPECT or 1 to 2 dysfunctional segments on stress echocardiography.

4) Coronary anatomy assessed by noninvasive tests (CCTA): High-risk findings include stenosis in the left main coronary artery, in the proximal section of the left anterior descending artery (LAD), or 3-vessel CAD. Intermediate-risk findings include 1-vessel or 2-vessel disease.

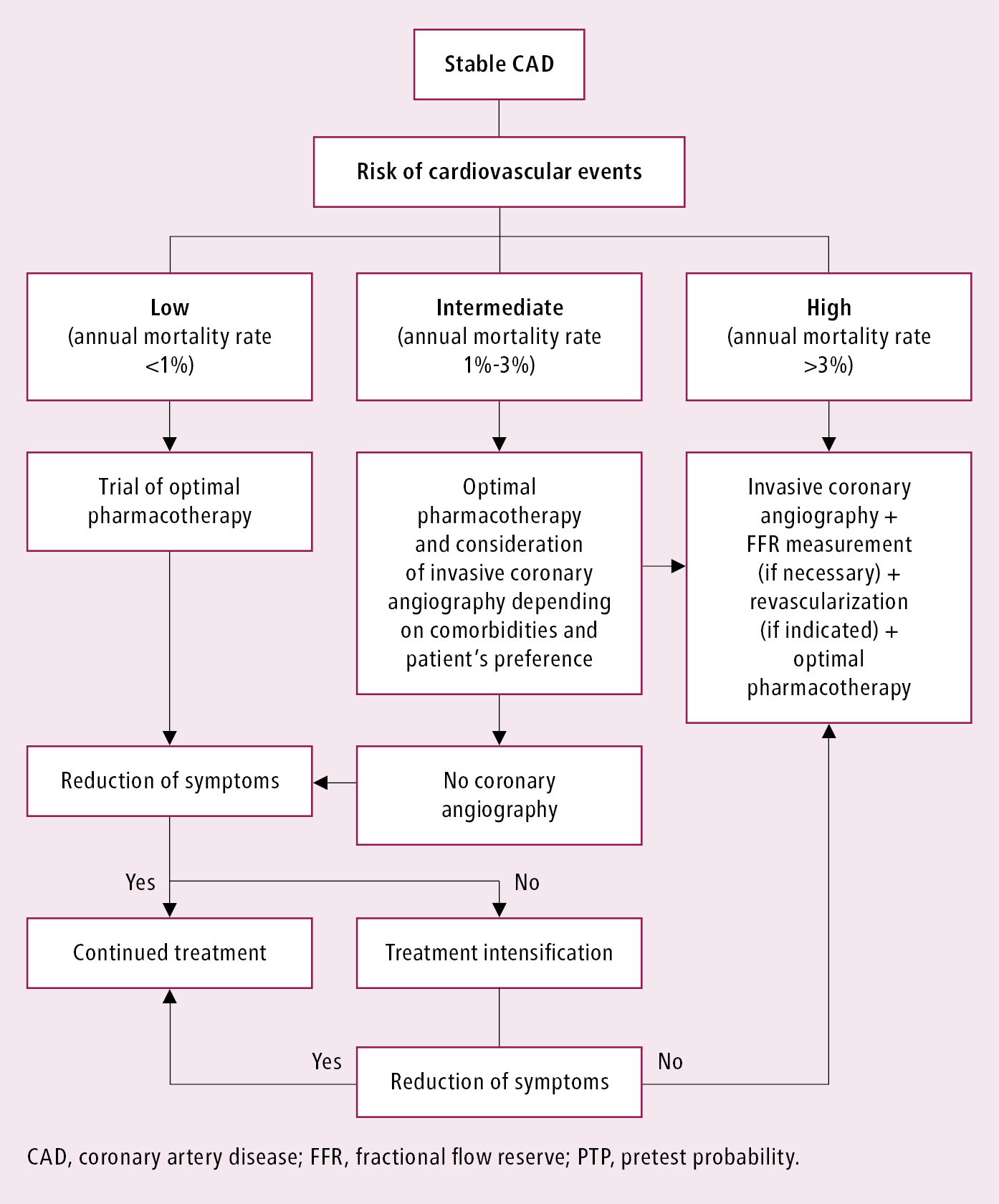

Management based on the estimated risk of a cardiovascular event: Table 3.11-11, Figure 3.11-4. In all patients with confirmed CAD optimal medical therapy should be started. The decision to proceed to coronary angiography and revascularization depends on the estimated risk, symptom control, and patient preference (see below).

Other causes of chest pain (see Chest Pain). Other causes of ST-segment and T-wave abnormalities.

TreatmentTop

1. Control of the risk factors of atherosclerosis (secondary prevention): see Prevention of Cardiovascular Diseases.

2. Treatment of conditions worsening angina, such as anemia, hyperthyroidism, rapid or excessive hormone replacement in hypothyroidism, or tachyarrhythmias.

3. Increasing physical activity (below the threshold of angina): 30 minutes daily ≥3 days a week.

4. Influenza vaccination: Annually.

5. Optimal medical therapy to improve prognosis and control the symptoms of angina.

6. Invasive treatment (percutaneous coronary intervention [PCI], coronary artery bypass grafting [CABG]): In eligible patients.

Optimal Medical Therapy: Treatment to Improve Prognosis

In every patient the following oral agents should be administered on a lifelong basis:

1) Antiplatelet agents: Acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) 75 to 81 mg once daily or a P2Y12 inhibitor (clopidogrel 75 mg daily); some meta-analyses suggest superiority of clopidogrel over ASA in this settingEvidence 3Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to imprecision. Gragnano F, Cao D, Pirondini L, et al. P2Y12 Inhibitor or Aspirin Monotherapy for Secondary Prevention of Coronary Events. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2023;82(2):89-105. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2023.04.051 (see Table 3.11-3). Combination therapy with ASA and clopidogrel is not recommended in stable patients except after stenting (see below).Evidence 4Strong recommendation (downsides clearly outweigh benefits; right action for all or almost all patients). High Quality of Evidence (high confidence that we know true effects of intervention). Antithrombotic Trialists' Collaboration. Collaborative meta-analysis of randomised trials of antiplatelet therapy for prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke in high risk patients. BMJ. 2002;324(7329):71-86. doi:10.1136/bmj.324.7329.71

2) Low-dose oral anticoagulants: ASA in addition to a low-dose oral anticoagulant (rivaroxaban 2.5 mg bid) may be considered as an added risk-reduction strategy in patients who are at elevated risk of future coronary events compared with bleeding events.Evidence 5Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). High Quality of Evidence (high confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Connolly SJ, Eikelboom JW, Bosch J, et al; COMPASS investigators. Rivaroxaban with or without aspirin in patients with stable coronary artery disease: an international, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2018 Jan 20;391(10117):205-218. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32458-3. Epub 2017 Nov 10. Erratum in: Lancet. 2017 Dec 21. PubMed PMID: 29132879.

3) Statins (see Table 3.12-1): Make attempts to lower LDL-C levels ≤1.8 mmol/L (<1.4 mmol/L according to the European Society of Cardiology [ESC]), and if this cannot be achieved, to reduce them by >50% compared with baseline levels.Evidence 6Strong recommendation (benefits clearly outweigh downsides; right action for all or almost all patients). High Quality of Evidence (high confidence that we know true effects of intervention). Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaboration, Baigent C, Blackwell L, Emberson J, et al. Efficacy and safety of more intensive lowering of LDL cholesterol: a meta-analysis of data from 170,000 participants in 26 randomised trials. Lancet. 2010 Nov 13;376(9753):1670-81. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61350-5. Epub 2010 Nov 8. PubMed PMID: 21067804; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2988224. In cases of poor tolerance or ineffectiveness of statins, the use of ezetimibe or proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors can be considered.

4) Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) (or angiotensin-receptor blockers [ARBs]) are indicated in patients with coexisting hypertension, DM, heart failure, or LV systolic dysfunction (dosage: Table 3.11-12).Evidence 7Strong recommendation (benefits clearly outweigh downsides; right action for all or almost all patients). High Quality of Evidence (high confidence that we know true effects of intervention). Yusuf S, Sleight P, Pogue J, Bosch J, Davies R, Dagenais G. Effects of an angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor, ramipril, on cardiovascular events in high-risk patients. The Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation Study Investigators. N Engl J Med. 2000 Jan 20;342(3):145-53. Erratum in: 2000 May 4;342(18):1376. N Engl J Med 2000 Mar 9;342(10):748. PubMed PMID: 10639539. Dagenais GR, Pogue J, Fox K, Simoons ML, Yusuf S. Angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors in stable vascular disease without left ventricular systolic dysfunction or heart failure: a combined analysis of three trials. Lancet. 2006 Aug 12;368(9535):581-8. Review. PubMed PMID: 16905022.

Optimal Medical Therapy: Treatment to Control Symptoms

1. Acute symptom control and prevention prior to planned exercise: Use a short-acting nitrate: nitroglycerin aerosol (Table 3.11-13). Patients should be instructed to use nitroglycerin 3 times at 5-minute intervals. If no relief is achieved, the patient should call an ambulance and should be assessed by the medical personnel for acute chest pain. Relative contraindications include hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with outflow tract obstruction, severe aortic stenosis, use of phosphodiesterase-5 (PDE-5) inhibitors (eg, sildenafil). Other drug interactions include alpha-blockers (in male patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia the combined use of nitrates and a selective alpha-blocker [tamsulosin] is allowed). Adverse effects: headache, facial flushing, dizziness, syncope.

2. Prevention of angina and increasing exercise tolerance:

1) Beta-blockers reduce heart rate, contractility, and atrioventricular (AV) conduction. They are the first-line agents for treatment of angina. Physicians should titrate the dose on the basis of heart rate and blood pressure with a goal to achieve the maximum recommended dose. Typical dosage: Table 3.11-14. A beta-blocker may be considered in asymptomatic patients with extensive ischemia (>10% of LV). Absolute contraindications: symptomatic bradycardia, symptomatic hypotension, second-degree or third-degree AV block, sick sinus syndrome, severe decompensated heart failure. Adverse effects: bradycardia, AV block, bronchospasm, peripheral artery spasm, and peripheral hypoperfusion in patients with severe peripheral artery disease; sexual dysfunction and loss of libido; and particularly in the case of propranolol, fatigue, headache, sleep disturbances, insomnia, vivid dreams, depression. Caution should be exercised in combining beta-blockers with verapamil and diltiazem due to their additive effects on AV conduction and heart rate.

2) Calcium channel blockers are smooth muscle vasodilators with a negative inotropic effect. They have a negative inotropic effect. They can be used in patients who cannot take beta-blockers or do not respond to monotherapy with a beta-blocker. Typical dosage: Table 3.11-14.

a) Diltiazem and verapamil lower the heart rate. They are of value in patients with contraindications to or intolerance of beta-blockers. Contraindications: heart failure, bradycardia, AV conduction disturbances, hypotension. Adverse effects: constipation, bradycardia, AV block, hypotension.

b) Dihydropyridines are vasodilators. Their mechanism of action is complementary to beta-blockers. They can be used in combination with a beta-blocker in patients not responding to a beta-blocker alone. Adverse effects: facial flushing, headache, peripheral edema.

3) Long-acting nitrates are arterial and venous vasodilators; they reduce the preload. Isosorbide dinitrate, isosorbide mononitrate, or nitroglycerin are recommended as second-line agents; typical dosage: Table 3.11-13. When administered bid, ensure ~10-hour intervals between the doses. The onset of action of nitroglycerin patches occurs a few minutes after they are attached; their antianginal effect is maintained for 3 to 5 hours.

3. Other agents, such as ivabradine, molsidomine, nicorandil, ranolazine, and trimetazidine, are used for their antianginal properties in some countries around the world.

Invasive Angiography and Revascularization

In patients with a diagnosis of stable angina based on noninvasive testing, invasive angiography is indicated for high-risk patients or those with severe or refractory symptoms to assess the potential for revascularization:

1) Invasive coronary angiography (with assessment by FFR measurement, when necessary) is recommended:

a) For risk stratification in patients with severe stable angina or with a high risk of cardiovascular events, especially if symptoms do not improve with medical therapy.

b) For patients with mild or no symptoms if noninvasive risk stratification suggests a high risk of cardiovascular events and revascularization has the potential to improve prognosis.

2) Invasive coronary angiography (with FFR measurement) should be considered in patients with inconclusive or conflicting noninvasive test results to obtain a definitive diagnosis and inform prognosis.

3) Invasive intracoronary microvascular testing (with assessment for microvascular dysfunction and coronary spasm, eg, with adenosine and acetylcholine provocation) should be considered for patients who have convincing ongoing anginal symptoms despite medical therapy without obstructive coronary disease to obtain a definitive diagnosis and direct therapy.

Findings of invasive angiography (extent and complexity of CAD, LV dysfunction) as well as clinical factors (age, comorbidities, history of DM) dictate the decision to perform revascularization and the choice of the revascularization strategy. In patients with multivessel disease the angiographic extent and complexity of CAD can be quantified using the SYNTAX score (www.syntaxscore.com). Decisions about the revascularization strategy are usually taken by an interventional cardiologist in consultation with a cardiovascular surgeon as part of the heart team approach.

1. PCI is the preferred treatment in patients with:

1) One-vessel disease (including the proximal section of the LAD) or 2-vessel disease that does not involve the proximal LAD.

2) Anatomic features of a low-risk lesion.

3) Comorbidities increasing the risk of cardiac surgery.

2. CABG is preferred in patients with:

1) Three-vessel disease and a SYNTAX score >22 or reduced LV function.

2) Patients with DM and multivessel disease.

3) Left main coronary artery stenosis combined with 2-vessel or 3-vessel disease in patients with a SYNTAX score >32.

3. Anatomic subsets where either PCI or CABG may be considered include patients with 2-vessel disease involving the proximal LAD, 3-vessel disease with a low SYNTAX score (<22), or left main coronary artery stenosis with limited CAD at other sites.

4. Patients after prior revascularization: In patients with prior CABG or with prior PCI presenting with in-stent restenosis, PCI is the preferred treatment option, unless angiographic complexity or the extent of the disease favors bypass surgery.

5. Patients with DM: Patients with DM are at increased risk of disease progression and cardiovascular events. Patients with DM and multivessel disease have a survival advantage with bypass surgery. PCI with drug-eluting stents (DESs) should be considered in patients with 1-vessel disease.Evidence 8Strong recommendation (benefits clearly outweigh downsides; right action for all or almost all patients). High Quality of Evidence (high confidence that we know true effects of intervention). Farkouh ME, Domanski M, Sleeper LA, et al; FREEDOM Trial Investigators. Strategies for multivessel revascularization in patients with diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2012 Dec 20;367(25):2375-84. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211585. Epub 2012 Nov 4. PubMed PMID: 23121323.

6. Patients with CKD: In patients with nonsevere CKD in whom CABG is indicated because of the extent of CAD, surgical risk is acceptable, and life expectancy justifies the procedure, consider CABG rather than PCI.

7. Intracoronary assessment: For patients without diagnostic noninvasive evidence of ischemia, FFR measurement with administration of IV or intracoronary adenosine may be used to guide revascularization decisions, especially in uncertain clinical situations, such as an angiographically moderate coronary stenosis or atypical symptoms. Revascularization is recommended in patients with angina, a positive stress test result, or with an FFR value <0.80, but it should be deferred in those with FFR >0.80.

Choice of Stents and Management After Stent Insertion

1. Choice of stents and antiplatelet therapy in patients undergoing elective PCI: Second-generation DESs with thinner struts and biodegradable or more biocompatible polymers have shown superior outcomes compared with first-generation DESs and BMSs. Dual antiplatelet therapy should be used for 6 months in patients undergoing elective PCI with DESs and continued for up to 3 years in patients in whom the risk of ischemic versus bleeding outcomes is favorable. Shortened duration of dual antiplatelet therapy of 1 to 3 months can be considered for those at high bleeding risk.Evidence 9Strong recommendation (benefits clearly outweigh downsides; right action for all or almost all patients). High Quality of Evidence (high confidence that we know true effects of intervention). Bangalore S, Toklu B, Amoroso N, et al. Bare metal stents, durable polymer drug eluting stents, and biodegradable polymer drug eluting stents for coronary artery disease: mixed treatment comparison meta-analysis. BMJ. 2013 Nov 8;347:f6625. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f6625. PubMed PMID: 24212107; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3898413. Tsigkas G, Apostolos A, Trigka A, et al. Very Short Versus Longer Dual Antiplatelet Treatment After Coronary Interventions: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2023;23(1):35-46. doi:10.1007/s40256-022-00559-0 Saito T, Fujisaki T, Aikawa T, et al. Strategy of dual antiplatelet therapy for patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction and non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Int J Cardiol. 2023;389:131157. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2023.131157 Dual antiplatelet therapy is recommended with aspirin and clopidogrel for patients undergoing stenting for chronic coronary disease. Ticagrelor or prasugrel should be chosen in combination with aspirin for patients presenting with acute coronary syndromes, stent thrombosis, or in other high-risk situations.

2. Antithrombotic treatment is recommended after stenting in patients with atrial fibrillation and a moderate or high risk of thromboembolism in whom the use of vitamin K antagonists or direct oral anticoagulants is necessary. The duration of dual antiplatelet therapy and/or triple therapy should be individualized based on the balance of risks of thrombosis and bleeding. Bleeding is minimized in regimens that limit the duration of triple therapy. Clopidogrel and an anticoagulant for long-term treatment combined with the use of ASA during the time of stent implantation and shortly afterwards may be preferred as compared with an extended course of triple therapy because of the elevated risk of bleeding with this approach.Evidence 10Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to imprecision. Cannon CP, Bhatt DL, Oldgren J, et al; RE-DUAL PCI Steering Committee and Investigators. Dual Antithrombotic Therapy with Dabigatran after PCI in Atrial Fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2017 Oct 19;377(16):1513-1524. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1708454. Epub 2017 Aug 27. PubMed PMID: 28844193. Lopes RD, Heizer G, Aronson R, et al; AUGUSTUS Investigators. Antithrombotic Therapy after Acute Coronary Syndrome or PCI in Atrial Fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2019 Apr 18;380(16):1509-1524. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1817083. Epub 2019 Mar 17. PubMed PMID: 30883055. Kuno T, Ueyama H, Takagi H, et al. Meta-analysis of Antithrombotic Therapy in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. Am J Cardiol. 2020;125(4):521-527. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2019.11.022

Follow-UpTop

Regular monitoring of modifiable risk factors: see Prevention of Cardiovascular Diseases. The frequency of follow-up visits depends on the severity of risk factors and angina: usually every 3 to 4 months in the first year of treatment, and then (in stable patients) every 6 months to 1 year.

PrognosisTop

The annual mortality rate is 1.2% to 3.8%, risk of cardiac death is 0.6% to 1.4%, and risk of nonfatal MI is 0.6% to 2.7%. Adverse prognostic factors include advanced age, more severe angina pectoris (Table 3.11-9), poor performance status, resting ECG abnormalities, silent myocardial ischemia, LV systolic dysfunction, extensive ischemia documented by noninvasive stress tests, advanced lesions observed in coronary angiography, DM, renal failure, LV hypertrophy, and resting heart rate >70 beats/min.

Tables and FiguresTop

|

Grade I: Ordinary physical activity (such as walking and climbing stairs) does not cause angina. Angina occurs with strenuous, rapid, or prolonged exertion at work or recreation. |

|

Grade II: A slight limitation of ordinary activity. Angina occurs when: – Walking or climbing stairs rapidly – Walking uphill – Walking or climbing stairs after meals, in cold, or in wind, or when under emotional stress, or only during the few hours after awakening – Walking >200 meters or climbing more than 1 flight of stairs at a normal pace and in normal conditions |

|

Grade III: Marked limitation of ordinary physical activity. Angina occurs when walking 100-200 meters or climbing 1 flight of stairs at a normal pace in normal conditions. |

|

Grade IV: Inability to carry on any physical activity without discomfort; anginal syndrome may be present at rest. |

|

Source: Canadian Cardiovascular Society. Canadian Cardiovascular Society grading of angina pectoris. www.ccs.ca. |

|

Symptom |

30-39 years |

40-49 years |

50-59 years |

60-69 years |

≥70 years |

|||||

|

M |

F |

M |

F |

M |

F |

M |

F |

M |

F |

|

|

Typical anginal pain |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Atypical anginal pain |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Nonanginal pain |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dyspneaa |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Dark red, PTP >15% (patients in whom noninvasive tests are most useful); light red, PTP 5%-15% (patients in whom diagnostic testing for CAD may be considered after the clinical probability has been assessed [see text]); grey, PTP <5%. a As the only or key symptom. |

||||||||||

|

Adapted from the 2020 European Society of Cardiology guidelines. |

||||||||||

|

CAD, coronary artery disease; PTP, pretest probability. |

||||||||||

|

Study |

Risk | ||

|

High |

Intermediate |

Low | |

|

ECG stress testa |

Annual cardiovascular mortality | ||

|

>3% |

1%-3% |

<1% | |

|

Imaging studies |

Area of ischemia | ||

|

>10%b |

1%-10%c |

– | |

|

Coronary CTA |

Coronary lesions | ||

|

Significant stenosisd |

Significant stenosise |

Normal coronary arteries or atherosclerotic plaques only | |

|

a Risk assessment using the Duke treadmill score including exercise workload in time expressed in metabolic equivalents, ST-T changes during and after exercise, and clinical symptoms (no angina, angina, or angina causing discontinuation of the test). Calculator available at www.cardiology.org/tools/medcalc/duke. b >10% in SPECT; the quantitative data for MRI are limited: probably ≥2 segments (out of 16) with new areas of hypoperfusion; ≥3 segments (out of 17) with dysfunction caused by dobutamine; or ≥3 segments (out of 17) with abnormal wall motion observed on stress echocardiography. c Or any ischemia rated as lower than high-risk on MRI of the heart or stress echocardiography. d That is, 3-vessel disease with proximal stenosis of the large coronary arteries, stenosis of the left main coronary artery, or proximal stenosis of the LAD. e Non–high-risk stenosis of proximal large coronary arteries. | |||

|

Adapted from Eur Heart J. 2013;34(38):2949-3003. | |||

|

CTA, computed tomography angiography; ECG, electrocardiography; LAD, left anterior descending artery; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; SPECT, single-photon emission computed tomography. | |||

|

Agent |

Dosage (PO) |

|

ACEIs | |

|

Benazepril |

10-40 mg once daily or in 2 divided doses |

|

Quinapril |

10-80 mg once daily or in 2 divided doses |

|

Cilazapril |

2.5-5 mg once daily |

|

Enalapril |

5-40 mg once daily or in 2 divided doses |

|

Fosinopril |

20-40 mg once daily or in 2 divided doses |

|

Imidapril |

5-20 mg once daily |

|

Captopril |

25-50 mg bid to tid |

|

Lisinopril |

10-40 mg once daily |

|

Moexipril |

7.5-30 mg once daily or in 2 divided doses |

|

Perindopril |

4(5)-8(10) mg once daily |

|

Ramipril |

2.5-5 mg once daily (max, 10 mg) |

|

Trandolapril |

2-4 mg once daily |

|

ARBs | |

|

Losartan |

50-100 mg once daily |

|

Valsartan |

80-320 mg once daily |

|

Candesartan |

8-32 mg once daily |

|

Telmisartan |

40-80 mg once daily |

|

Irbesartan |

150-300 mg once daily |

|

Eprosartan |

600-800 mg once daily |

|

Olmesartan |

20-40 mg once daily |

|

bid, 2 times a day; PO, oral; tid, 3 times a day. | |

|

Agent |

Preparations |

Dosagea |

Duration of action |

|

Nitroglycerin (INN glyceryl trinitrate) |

Aerosol |

0.4 mg |

1.5-7 min |

|

Transdermal patch |

5-20 mg/24 h (patch should be detached for the night) |

| |

|

Prolonged-release tablets |

6.5-15 mg bid |

4-8 h | |

|

Isosorbide dinitrate |

Tablets |

5-10 mg |

Up to 60 min |

|

Isosorbide mononitrate |

Tablets |

10-40 mg bid |

Up to 8 h |

|

Prolonged-release tablets |

50-100 mg once daily |

12-24 h | |

|

Prolonged-release capsules |

40-120 mg once daily |

||

|

a In a long-term bid administration, the second dose should be administered within 8 h of the first dose (eg, 7:00 and 15:00), and the nitroglycerin patches should be detached for 10 h. | |||

|

bid, 2 times a day; INN, international nonproprietary name. | |||

|

Agent |

Dosage (PO) |

||

|

Beta-blockers |

|||

|

Acebutolol |

200-600 mg bid |

||

|

Atenolol |

50-200 mg once daily |

||

|

Betaxolol |

10-20 mg once daily |

||

|

Bisoprolol |

5-10 mg once daily |

||

|

Carvedilol |

12.5-25 mg bid |

||

|

Metoprolol |

|||

|

Immediate-release formulations |

25-100 mg bid |

||

|

Extended-release formulations |

25-200 mg once daily |

||

|

Pindolol |

2.5-10 mg bid or tid |

||

|

Propranolol |

10-80 mg bid or tid |

||

|

Dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers |

|||

|

Amlodipine |

5-10 mg once daily |

||

|

Felodipine |

5-10 mg once daily |

||

|

Nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers |

|||

|

Diltiazem |

|

||

|

Immediate-release formulations |

30-90 mg tid |

||

|

Extended-release formulations |

120-480 mg once daily (or in 2 divided doses) |

||

|

Verapamil |

|||

|

Immediate release formulations |

40-160 mg tid |

||

|

Extended-release formulations |

120-480 mg once daily |

||

|

Other |

|||

|

Nicorandil |

10-20 mg bid |

||

|

bid, 2 times a day; tid, 3 times a day; PO, oral. |

|||

Figure 3.11-3. Proposed diagnostic algorithm in patients with suspected stable coronary artery disease.

Figure 3.11-4. Management algorithm in patients with confirmed stable coronary artery disease depending on the risk of cardiovascular events.