Joglar JA, Chung MK, Armbruster AL, et al; Peer Review Committee Members. 2023 ACC/AHA/ACCP/HRS Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Atrial Fibrillation: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2024 Jan 2;149(1):e1-e156. PMID: 38033089.

Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA Guideline for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2021 Feb 2;143(5):e35-e71. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000932. Epub 2020 Dec 17. Erratum in: Circulation. 2021 Feb 2;143(5):e228. Erratum in: Circulation. 2021 Mar 9;143(10):e784. PMID: 33332149.

Baumgartner H, Falk V, Bax JJ, et al; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2017 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2017 Sep 21;38(36):2739-2791. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx391. PMID: 28886619.

Definition, Etiology, PathogenesisTop

Mitral stenosis (MS) is a reduction of the mitral valve orifice area causing obstruction of blood flow from the left atrium to the left ventricle (LV). Classification based on etiology:

1) Structural MS: Limited mobility of the leaflets and chordae tendineae due to organic lesions. Etiology: rheumatic (most frequently, especially if more than mild), degenerative/nonrheumatic/calcific (due to severe mitral annular calcification [MAC], increasingly common in aging populations), infective endocarditis; rarely, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, carcinoid syndrome, or storage diseases.

2) Functional MS: Inhibited opening of structurally normal valve leaflets. Etiology: aortic regurgitation, left atrial thrombus, tumor (most commonly left atrial myxoma).

Clinical Features and Natural HistoryTop

1. Symptoms: Impaired exercise tolerance, fatigue, exertional dyspnea, sometimes cough with expectoration of frothy sputum, hemoptysis, recurrent respiratory tract infections, palpitations, right upper abdominal quadrant discomfort, rarely hoarseness (due to compression of the left recurrent laryngeal nerve by an enlarged left atrium [Ortner syndrome]), chest pain (in 15% of patients due to high right ventricular pressures or coexisting coronary artery disease).

2. Signs: An accentuated first heart sound, opening snap (OS) of the mitral valve, a low-pitched decrescendo diastolic rumble with presystolic accentuation in sinus rhythm (the timing of onset and loudness of the OS vary with left atrial pressure and compliance of leaflets). A Graham Steell murmur caused by pulmonary regurgitation in patients with severe pulmonary hypertension and dilation of the main pulmonary artery. In advanced MS, pinkish-purple patches on the cheeks, peripheral cyanosis, systolic pulsation in the epigastrium, displacement of the apical impulse to the left, symptoms of right ventricular failure (see Chronic Heart Failure).

3. Natural history: The severity of MS gradually increases. The first symptoms usually develop ~15 to 20 years after an episode of rheumatic fever. The usual presenting symptoms are exertional dyspnea; supraventricular arrhythmias (particularly atrial fibrillation [AF]; the risk increases with age and with progressive left atrial enlargement); and thromboembolic events (up to 6/100 patients); risk factors: age, AF, small mitral valve orifice area, spontaneous left atrial contrast on echocardiography.

DiagnosisTop

Diagnosis is based on typical clinical features and echocardiography results.

1. Electrocardiography (ECG): Features of left atrial enlargement, often P mitrale, frequently atrial arrhythmias, particularly AF. In patients with pulmonary hypertension, right axis deviation, incomplete right bundle branch block (less frequently other features of right ventricular hypertrophy and overload), P mitrale that may evolve into P cardiale or P pulmonale.

2. Chest radiography (Figure 3.18-5): Left atrial enlargement, dilation of the upper lobe pulmonary veins, dilation of the main pulmonary artery, pulmonary alveolar edema, pulmonary interstitial edema, right ventricular enlargement, calcifications of the mitral valve (rare).

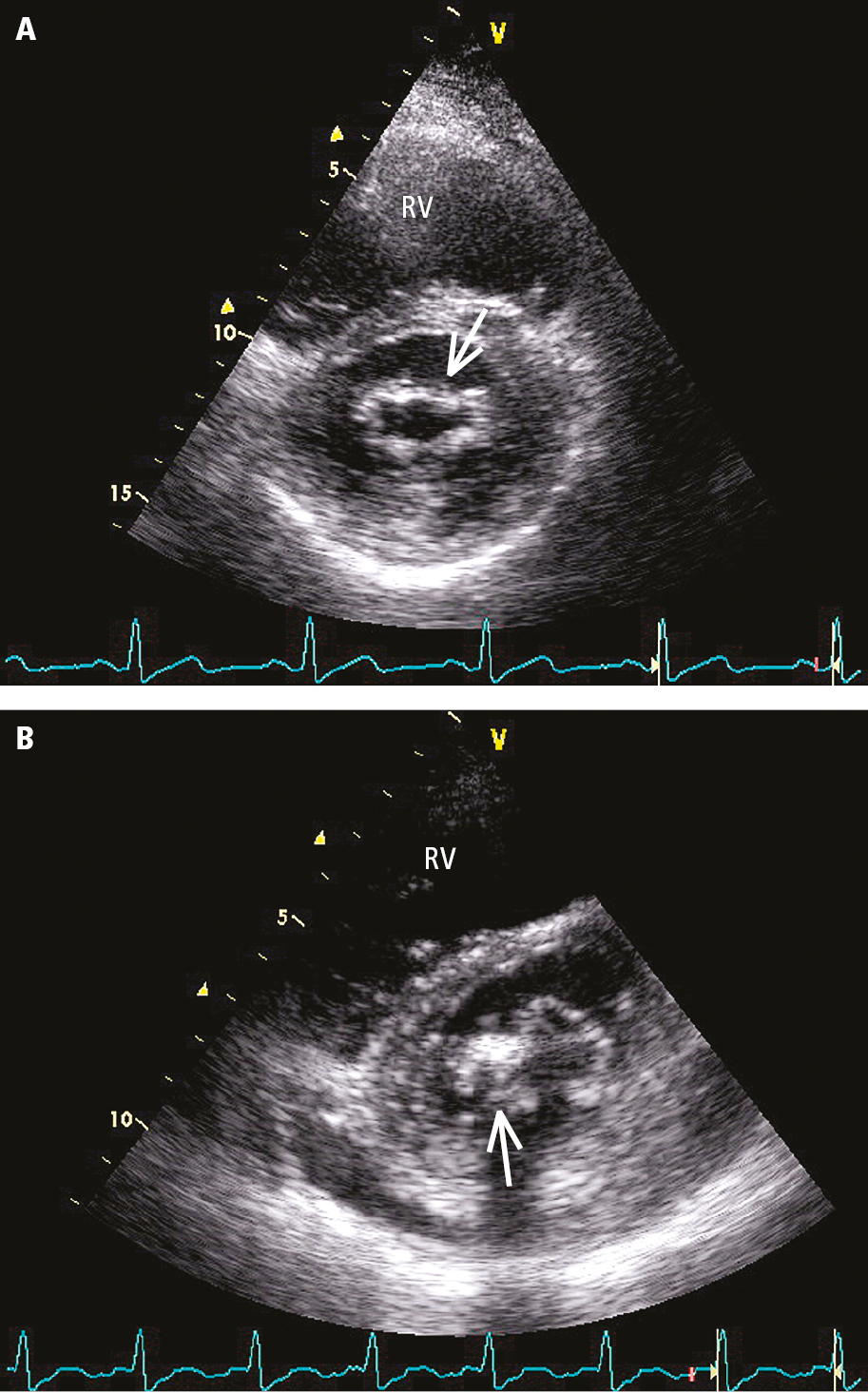

3. Echocardiography (Figure 3.18-6 and Figure 3.18-7) is used to evaluate the anatomic features of the valve (define the mechanism and suitability of percutaneous mitral balloon commissurotomy), detect left atrial thrombi (transesophageal echocardiography [TEE] is useful as most thrombi occur in the left atrial appendage, which is not well-visualized on transthoracic echocardiography [TTE]), define the severity (measure the mean transvalvular gradient, calculate the mitral valve area [MVA]), estimate the pulmonary artery pressure, and detect concurrent mitral regurgitation or the presence of other structural heart disease (Table 3.18-8).

4. Exercise stress testing is used to assess exercise tolerance, with stress echocardiography performed to assess associated changes in pulmonary artery pressures and mean gradients (especially important for management of patients with moderate MS at rest and disproportionate exertional symptoms).

5. Cardiac catheterization and coronary angiography are infrequently used in cases that are equivocal by clinical and echocardiographic criteria to confirm the severity of MS and to measure pulmonary artery pressures. Coronary angiography is recommended in patients >40 years of age who are undergoing intervention for MS (see below), or in younger patients with LV dysfunction or suspected coronary artery disease.

TreatmentTop

1. Mild asymptomatic MS: Pharmacologic treatment.

2. Moderate or severe MS: Management depends primarily on the presence of symptoms and anatomy of the valve. Specialist referral is usually required; however, in general, the following factors need to be analyzed when structural intervention is considered: severity of stenosis, severity of symptoms, valve morphology (rheumatic vs nonrheumatic, suitability for percutaneous intervention), individual surgical risk, presence of other structural heart diseases.

1. Percutaneous balloon mitral commissurotomy (PBMC), also referred to as percutaneous balloon mitral valvuloplasty (PBMV): Separation or tearing apart of the fused commissures with a balloon through a catheter inserted by venous access via an interatrial septal puncture. Owing to high efficacy and low risk of complications (death, cardiac tamponade, peripheral embolism), it is the first therapeutic choice for appropriate MS cases.Evidence 1Strong recommendation (benefits clearly outweigh downsides; right action for all or almost all patients). Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to a limited number of patients enrolled in studies (imprecision). Ben Farhat M, Ayari M, Maatouk F, et al. Percutaneous balloon versus surgical closed and open mitral commissurotomy: seven-year follow-up results of a randomized trial. Circulation. 1998 Jan 27;97(3):245-50. PMID: 9462525.

Indications: Patients with severe MS (MVA <1.5 cm2) with symptoms attributable to MS (also asymptomatic patients with new-onset AF, pulmonary artery systolic pressure [PASP] >50 mm Hg, or planning pregnancy), less than moderate mitral regurgitation (2+), and valve anatomy amenable to PBMC (less calcified, mobile valves with primary pathology and tips of the leaflets with minimal subvalvular involvement are generally amenable to PBMC, whereas heavily calcified, immobile valves require surgical treatment). Formalized echocardiographic morphologic assessments have been developed to predict optimal results by PBMV, with the Wilkins score being the most widely used.

Contraindications: MVA >1.5 cm2; left atrial thrombus; concomitant moderate or greater mitral regurgitation; nonrheumatic etiology of MS; poorly mobile valves; severe leaflet or bicommissural calcification; absence of commissural fusion; severe concomitant aortic valve disease, or severe combined tricuspid stenosis and regurgitation requiring surgical intervention; concomitant coronary artery disease requiring bypass surgery.

2. Surgical valve repair:

1) Open (direct vision) mitral commissurotomy using cardiopulmonary bypass.

2) Closed mitral commissurotomy using a transatrial approach (this is rarely if ever used).

3. Mitral valve replacement (MVR) is indicated in patients with rheumatic mitral stenosis, New York Heart Association (NYHA) class III/IV heart failure (HF), and severe abnormalities of the valvular apparatus when balloon and surgical commissurotomy are not possible. The type of replacement valve (bioprosthetic vs mechanical) will be chosen based on informed decision making involving the patient and treating physicians, weighing the pros and cons of each type of valve (eg, durability and need for long-term systemic anticoagulation). For nonrheumatic calcific MS, PBMC is not an option. Mitral valve surgery can be considered in severely symptomatic patients after informed discussions with the patient given the poor overall prognosis in this population, high surgical risk, and technical challenges of surgical intervention. Transcatheter interventional options in this high-risk population are currently being evaluated (valve-in-MAC). In patients with mechanical valves, lifetime oral anticoagulant treatment is necessary (target international normalized ratio [INR] values: see Table 3.18-5).

1. Patients not eligible for or refusing consent to invasive treatment: Diuretics (in the case of symptoms of pulmonary congestion), beta-blockers, nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers, ivabradine, and digoxin (to decrease transmitral gradients and improve dyspnea, reduce heart rate with digoxin primarily in the case of AF with a fast ventricular rhythm with or without LV dysfunction), and guideline-directed medical therapy in the case of coexisting LV dysfunction.

2. Anticoagulant treatment: For rheumatic MS or moderate to severe MS, warfarin is the anticoagulant of choice with a target INR of 2.0-3.0. In patients with rheumatic MS, the presence of AF, after embolic events, or with a documented left atrial thrombus, anticoagulation is indicated. In patients with an enlarged left atrium (>55 mm) or spontaneous left atrial contrast on echocardiography, anticoagulation may be considered but is not supported by evidence.

3. Electrical cardioversion: In patients with AF and hemodynamic instability. Electrical cardioversion may be considered in the case of the first AF occurrence in patients with mild to moderate MS, and after successful invasive treatment of MS in patients with a short episode of AF and minor left atrial enlargement. If medical therapy fails and AF is producing HF, clinical instability, or both, electrical cardioversion can be considered in patients with MS who are therapeutically anticoagulated; transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) may also be helpful in such patients to exclude left atrial and left atrial appendage thrombi prior to cardioversion, particularly those with severe MS and marked left atrial enlargement. Pharmacologic cardioversion (usually with amiodarone) is generally less effective than electrical.

4. Prevention of infective endocarditis and of recurrent rheumatic fever (duration of antibiotic treatment depends on the presence of residual rheumatic valve changes post rheumatic fever and patient’s age).

Follow-UpTop

The frequency of follow-up visits in patients receiving noninvasive treatment depends on the severity of MS. Patients with mild asymptomatic MS: follow-up visits every 2 to 3 years. Asymptomatic patients with significant MS and patients after successful PBMC: clinical and echocardiographic examination every year; in symptomatic patients, every 6 months.

PrognosisTop

In asymptomatic patients the 10-year survival rates are >80% and 20-year survival rates are ~40%. The prognosis is affected by the onset of even minor symptoms and significantly improved by PBMC or MVR in patients with severe MS, symptoms attributable to MS, or both. The causes of death are HF and thromboembolic events.

Tables and FiguresTop

|

|

Stenosis | ||

|

Mild |

Moderate |

Severe | |

|

Mean MVG (mm Hg) |

<5 |

5-10 |

>10 |

|

PASP (mm Hg) |

<30 |

30-50 |

>50 |

|

MVA (cm2) |

>2.0 |

1.5-2.0 |

<1.5 (<1.0: very severe) |

|

Based on Circulation 2021;143(5): e72-e227. | |||

|

MVA, mitral valve area; MVG, mitral valve gradient; PASP, pulmonary artery systolic pressure. | |||

Figure 3.18-7. Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) (parasternal short-axis view above the mitral valve orifice) of a patient with mitral valve stenosis: A, mild, evenly distributed fibrosis of mitral valve leaflets (arrow); B, localized thickening and fibrosis of mitral valve leaflets, calcification of the posterior commissure (arrow). RV, right ventricle.