Hategan A, Saperson K, Harms S, Waters H, eds. Humanism and Resilience in Residency Training: A Guide to Physician Wellness. Springer International Publishing; 2020. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-45627-6.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; National Academy of Medicine; Committee on Systems Approaches to Improve Patient Care by Supporting Clinician Well-Being. Taking Action Against Clinician Burnout: A Systems Approach to Professional Well-Being. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2019 Oct 23. PMID: 31940160.

American Hospital Association. Well-Being Playbook: A Guide for Hospital and Health System Leaders. May 2019. Accessed May 1, 2020. https://www.aha.org/system/files/media/file/2019/05/plf-well-being-playbook.pdf.

Thomas LR, Ripp JA, West CP. Charter on Physician Well-being. JAMA. 2018 Apr 17;319(15):1541-1542. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.1331. PMID: 29596592.

Neff K, Germer C. The Mindful Self-Compassion Workbook: A Proven Way to Accept Yourself, Build Inner Strength, and Thrive. The Guilford Press; 2018.

West CP, Dyrbye LN, Erwin PJ, Shanafelt TD. Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016 Nov 5;388(10057):2272-2281. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31279-X. Epub 2016 Sep 28. PMID: 27692469.

Dolan ED, Mohr D, Lempa M, et al. Using a single item to measure burnout in primary care staff: a psychometric evaluation. J Gen Intern Med. 2015 May;30(5):582-7. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-3112-6. Epub 2014 Dec 2. PMID: 25451989; PMCID: PMC4395610.

West CP, Dyrbye LN, Sloan JA, Shanafelt TD. Single item measures of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization are useful for assessing burnout in medical professionals. J Gen Intern Med. 2009 Dec;24(12):1318-21. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1129-z. Epub 2009 Oct 3. PMID: 19802645; PMCID: PMC2787943.

Halbesleben JRB, Demerouti E. The construct validity of an alternative measure of burnout: Investigating the English translation of the Oldenburg Burnout Inventory. Work & Stress. 2005;19(3):208-20. doi: 10.1080/02678370500340728.

IntroductionTop

Physician health and wellness encompasses resilience, quality of life, as well as optimal physical, emotional, and mental well-being. It is increasingly recognized as crucial to achieving sustainability within medicine. Well physicians foster more effective and efficient health-care systems and cultivate healthier workplace cultures, which in turn promote the well-being of one’s colleagues and teams. Well physicians ultimately provide better care to their patients. However, it often remains a challenge for physicians to take care of themselves, while the responsibilities and stresses they face are persistent and unrelenting. These problems have continued to grow particularly in light of increasing system demands, technological advancements, and during public health crises, such as the current coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) global pandemic.

This chapter reviews the features of physician burnout, which remains endemic within medical communities and continues to pose a significant challenge to physician wellness. Strategies to help mitigate stress and burnout and optimize one’s own well-being will be shared, which can be implemented prophylactically when well or as an acute intervention when psychologically injured.

While the strategies shared within this chapter will focus on those that can be implemented at the individual level, the authors fully recognize that addressing the burnout issue requires change at the system level. As readers are encouraged to consider how they may contribute to and advocate for this change, the strategies provided here can be used in the interim as harm reduction and a temporizing measure while awaiting larger-scale solutions and interventions that more robustly address the roots of the problem.

Definition and Clinical FeaturesTop

Burnout was recognized in 2019 by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a global occupational phenomenon. Following suit, the 11th revision of the International Classification of Diseases and Health-Related Problems (ICD-11) described burnout not as a medical condition but rather a syndrome resulting specifically from occupation-related stress.

Burnout is further characterized by 3 core dimensions (Table 1):

1) Emotional exhaustion: Considered the most common and critical feature of burnout, resulting from perception of persistent work overload, akin to an analogy of running on an empty tank.

2) Depersonalization: Considered to be a method to cope with unrelenting job stress and strain in which one distances themselves from their work and views others, including patients, more impersonally.

3) Reduced sense of self-efficacy or personal accomplishment: Considered sequelae to the other two features, leading one to question or lose sight of the value and meaning of their work.

EpidemiologyTop

Burnout was first described among those in caregiving roles. Further research has shown that it is a phenomenon commonly associated with the field of medicine. Individuals enter medical training with lower rates of burnout and higher quality of life compared with other college graduates, but this trend soon reverses.

Burnout first emerges in medical school and peaks in residency, with >60% of trainees reporting burnout at any given time. Completing training does not end the battle, as burnout continues to affect practicing physicians, regardless of their stage of career, at rates varying in the literature between 30% and 50%. Physicians consistently experience higher rates of burnout and work-life balance dissatisfaction compared with the employed general population. Factors associated with a higher risk of burnout in medicine: Table 2.

PathogenesisTop

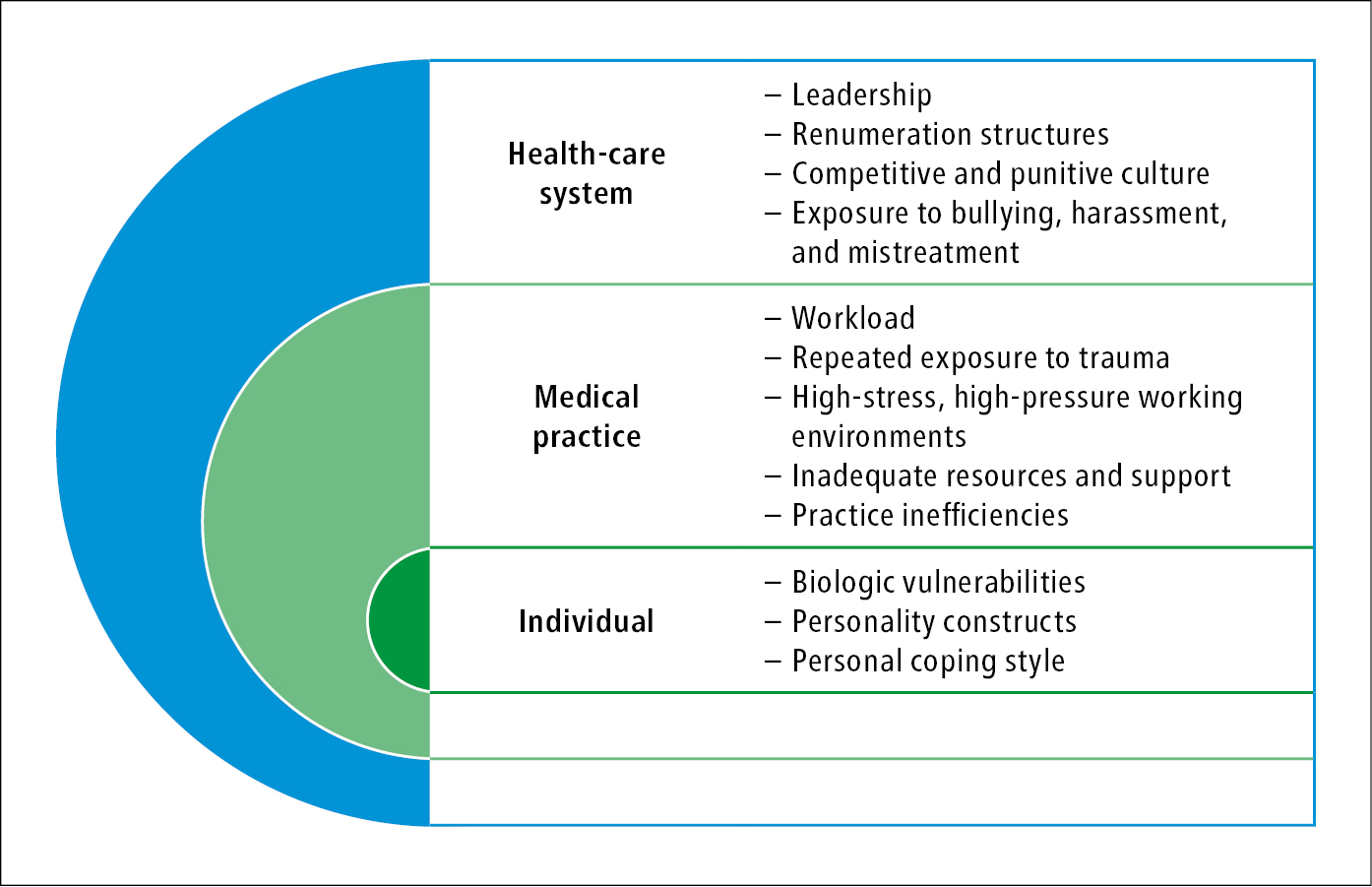

The purported causes are multifactorial in nature, often precipitated by a mix of factors at the level of the individual, medical practice, and health-care system as a whole (Figure 1).

Burnout is often further perpetuated and compounded by barriers to seeking care. The most commonly reported barriers include:

1) Lack of knowledge of supports available as well as lack of time or control over one’s schedule to access these.

2) Stigma around mental health that lingers in medicine and is portrayed by other health-care providers or society, leading many to suffer in silence and believe their struggles are self-imposed or an inherent weakness. Self-stigma is also problematic and occurs when these stigmatizing ideas are internalized by a provider, leading one to minimize their difficulties.

3) Fears of repercussions and lack of confidentiality, which are also prominent worries raised by health-care providers. Many express concern that seeking help or disclosing their stress and struggles may have a negative impact on evaluations, licensing, and career and leadership opportunities. Physicians who may need to take time off also are often hesitant to do so for fears of how this will be perceived by others, including how this may impact their patients, and by their colleagues.

ComplicationsTop

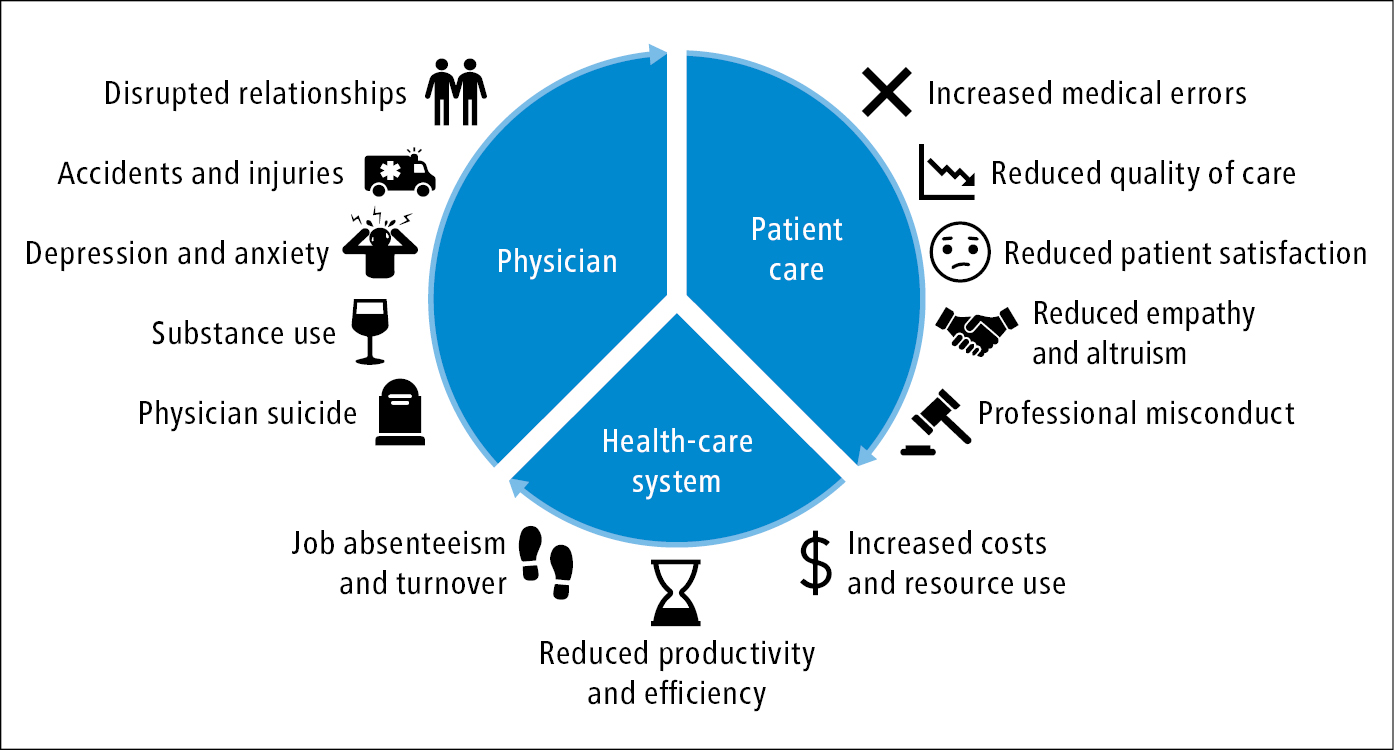

If burnout persists and is left unaddressed, it can result in an array of ill sequelae that may affect the physician and their patients as well as add further stress to an already overtaxed system (Figure 2).

IdentificationTop

As with any disease or illness entity in medicine, a favorable prognosis often is dependent on early detection and management. Similarly, the earlier burnout is recognized and managed, the better. However, prediction and identification of burnout is poor even among trained physicians, which may be due to a multitude of factors, including self-stigma.

While the gold standard for identifying and measuring burnout remains the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI), this well-validated questionnaire is lengthy, costly, and difficult to access. However, several alternative tools and scales have been developed to facilitate self-screening and recognition of those who may be at elevated risk of this syndrome. Recent efforts have also focused on adapting these aids to specifically meet the needs of health-care professionals. The most common screening tools: Table 3.

However, the key to timely identification is less about the tool or approach used to identify the signs and symptoms of burnout or stress and more about regularly taking time to check in with oneself, whether by using a formal scale, a mental health continuum such as those shared by the Resident Doctors of Canada or the Department of National Defence, or simply by taking a few moments to ask yourself how you are doing. All these serve to build self-awareness and reconnect one to their needs at that time to foster well-being.

ManagementTop

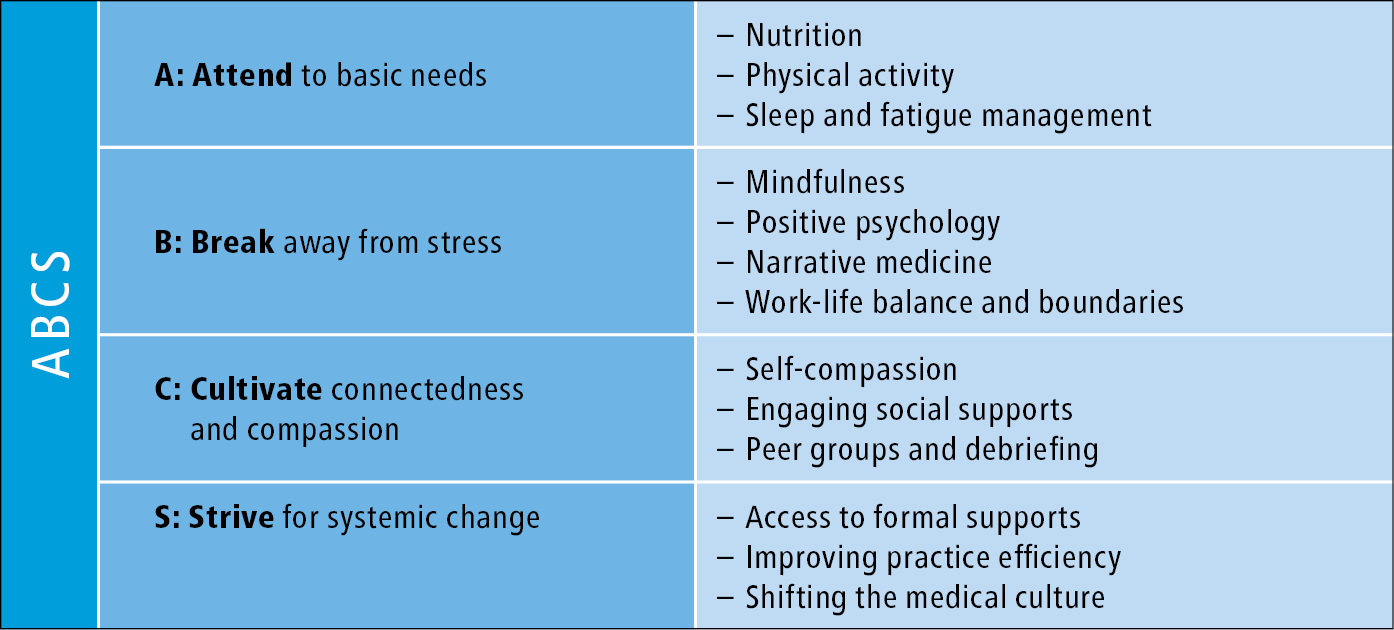

When stress and burnout arise, it can feel overwhelming and be hard to see through the clouds. In times like these, go back to the basics and use the “ABCS” (Figure 3) to help cope, as outlined below.

1. Eat a healthy diet: Eating a balanced diet and making mindful choices with regard to food selection can be beneficial in protecting against weight gain and chronic diseases as well as promoting optimal cognitive functioning, mood, and mental well-being.

1) Canada’s Food Guide, developed by Health Canada, strongly recommends a diet rich in vegetables, fruit, whole grains, and protein-rich foods to reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease, dyslipidemia, and hypertension. Limiting processed food as well as added sugar, sodium, saturated fats, and alcohol is also encouraged.Evidence 1Strong recommendation (benefits clearly outweigh downsides; right action for all or almost all patients). Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to heterogeneity, indirectness, and imprecision. Health Canada. Evidence Review for Dietary Guidance: Summary of Results and Implications for Canada’s Food Guide. October 2016. Accessed May 15, 2020. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/publications/food-nutrition/evidence-review-dietary-guidance-summary-results-implications-canada-food-guide.html Health Canada. Food, Nutrients and Health: Interim Evidence Update 2018. January 22, 2019. Accessed May 15, 2020. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/canada-food-guide/resources/evidence/food-nutrients-health-interim-evidence-update-2018.html

2) The Mediterranean diet is recommended because it improves cognitive functioning and reduces rates of cognitive decline and cardiovascular disease. This diet typically consists of vegetables, fruit, legumes, whole grains, nuts and seeds, healthy fats (olive oil), and fish. Poultry and dairy are consumed in moderation and intake of red meat is limited.Evidence 2Strong recommendation (benefits clearly outweigh downsides; right action for all or almost all patients). Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to heterogeneity, with a small number of studies reporting minimal harms for primary prevention and paucity of evidence for secondary prevention. Rees K, Takeda A, Martin N, et al. Mediterranean-style diet for the primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019 Mar 13;3(3):CD009825. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009825.pub3. PMID: 30864165; PMCID: PMC6414510. Psaltopoulou T, Sergentanis TN, Panagiotakos DB, Sergentanis IN, Kosti R, Scarmeas N. Mediterranean diet, stroke, cognitive impairment, and depression: A meta-analysis. Ann Neurol. 2013 Oct;74(4):580-91. doi: 10.1002/ana.23944. Epub 2013 Sep 16. PMID: 23720230.

3) Additional tips for the physician: Home-cooked meals are preferable to processed or pre-prepared foods, such as those from restaurants or cafeterias. Consider spending time once per week meal prepping. Time can also be saved by buying precut or washed products and using meal preparation or grocery delivery services.

2. Take regular nutrition breaks: The timing and regularity of one’s meals and snacks is important to maintaining the blood sugar level throughout the day, in addition to optimizing one’s physical and mental energy, mood, and cognitive performance.

1) Breakfast, particularly one that is low in glycemic load, remains one of the most important meals of the day. Combined with regular meals and snacks throughout the day, it provides the nutrients needed to function optimally.Evidence 3Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Low Quality of Evidence (low confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to heterogeneity, small sample sizes, and lack of randomization. Lemaire JB, Wallace JE, Dinsmore K, Roberts D. Food for thought: an exploratory study of how physicians experience poor workplace nutrition. Nutr J. 2011 Feb 18;10(1):18. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-10-18. PMID: 21333008; PMCID: PMC3068081. Lemaire JB, Wallace JE, Dinsmore K, Lewin AM, Ghali WA, Roberts D. Physician nutrition and cognition during work hours: effect of a nutrition based intervention. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010 Aug 17;10:241. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-241. PMID: 20712911; PMCID: PMC2929232.

2) For those working shifts or spending nights on call, avoid eating large meals between midnight and 6:00. This helps to avoid disrupting the circadian rhythm as well as prevent weight gain and other metabolic disorders.Evidence 4Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Low Quality of Evidence (low confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to limited studies, most of which were based on animal models. Lowden A, Moreno C, Holmbäck U, Lennernäs M, Tucker P. Eating and shift work - effects on habits, metabolism and performance. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2010 Mar;36(2):150-62. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.2898. Epub 2010 Feb 9. PMID: 20143038. Souza RV, Sarmento RA, de Almeida JC, Canuto R. The effect of shift work on eating habits: a systematic review. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2019 Jan 1;45(1):7-21. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.3759. Epub 2018 Aug 8. PMID: 30088659.

3) Additional tips for the physician: If you are unable to schedule time in to eat during your clinical day, consider carrying snacks with you to eat on the go.

3. Stay hydrated: Dehydration, while not an uncommon occurrence during busy shifts, can have significant impacts on our well-being. Maintaining adequate hydration is strongly recommended because it can help avoid fatigue, avoid impaired memory, and improve alertness, concentration, and reaction time.

1) Adequate daily fluid intake from all sources (including food, which supplies ~20% of oral intake) is approximately 3.7 L a day for men and 2.7 L a day for women. Consider starting with a reasonable goal of 8 × 8, consuming 8 glasses of water, 8 oz or 240 mL each, throughout the day.Evidence 5Strong recommendation (benefits clearly outweigh downsides; right action for all or almost all patients). Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to heterogeneity and imprecision. Goodman SPJ, Moreland AT, Marino FE. The effect of active hypohydration on cognitive function: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Physiol Behav. 2019 May 15;204:297-308. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2019.03.008. Epub 2019 Mar 12. PMID: 30876770. Cousins AL, Young HA, Thomas AG, Benton D. The Effect of Hypo-Hydration on Mood and Cognition Is Influenced by Electrolyte in a Drink and Its Colour: A Randomised Trial. Nutrients. 2019 Aug 24;11(9):2002. doi: 10.3390/nu11092002. PMID: 31450591; PMCID: PMC6769552.

2) Additional tips for the physician: Bring a water bottle with you to work if you can and try taking sips every hour. These can often be refilled from fountains or filling stations in hospitals and clinics.

Engage in exercise regularly: Regular exercise enhances physical health and reduces the risk of various chronic and metabolic diseases as well as premature death. Exercise can promote your mood, cognition, sleep, and general quality of life.

1) Canadian Physical Activity Guidelines strongly recommend for most adults (aged 18-64 years) to engage in a minimum of 150 minutes of moderate to vigorous activity in bouts ≥10 minutes every week. Those who are pregnant, have a disability, or have a medical condition should consult with a physician before beginning an exercise regimen. For those who may be sedentary, consider gradually working up to this target by setting smaller goals to prevent injury.Evidence 6Strong recommendation (benefits clearly outweigh downsides; right action for all or almost all patients). High Quality of Evidence (high confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology. Canadian Physical Activity Guidelines for Adults (18-64 years). Accessed May 14, 2020. https://csepguidelines.ca/adults-18-64/. Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology. Canadian Physical Activity Guidelines: Clinical Practice Guideline Development Report. January 2011. Accessed May 14, 2020. https://csepguidelines.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/CPAGuideline_Report_JAN2011.pdf. Warburton DE, Nicol CW, Bredin SS. Health benefits of physical activity: the evidence. CMAJ. 2006 Mar 14;174(6):801-9. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.051351. PMID: 16534088; PMCID: PMC1402378.

2) Resistance training, involving moving one’s limbs against resistance (which can be provided by gravity, one’s body weight, or resistance bands or weights), helps to strengthen muscles and bones. Adults (aged 18-64 years) are recommended to engage in such exercise 2 to 4 days per week.Evidence 7Strong recommendation (benefits clearly outweigh downsides; right action for all or almost all patients). High Quality of Evidence (high confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology. Canadian Physical Activity Guidelines for Adults (18-64 years). Accessed May 14, 2020. https://csepguidelines.ca/adults-18-64/. Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology. Canadian Physical Activity Guidelines: Clinical Practice Guideline Development Report. January 2011. Accessed May 14, 2020. https://csepguidelines.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/CPAGuideline_Report_JAN2011.pdf. Warburton DE, Nicol CW, Bredin SS. Health benefits of physical activity: the evidence. CMAJ. 2006 Mar 14;174(6):801-9. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.051351. PMID: 16534088; PMCID: PMC1402378.

3) Flexibility training, such as taking time to regularly stretch or engage in yoga, can help to improve balance, reducing one’s risk of falls, as well as enhance mobility and overall functioning. It is recommended that adults engage in such training 4 to 7 days a week.Evidence 8Strong recommendation (benefits clearly outweigh downsides; right action for all or almost all patients). High Quality of Evidence (high confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology. Canadian Physical Activity Guidelines for Adults (18-64 years). Accessed May 14, 2020. https://csepguidelines.ca/adults-18-64/. Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology. Canadian Physical Activity Guidelines: Clinical Practice Guideline Development Report. January 2011. Accessed May 14, 2020. https://csepguidelines.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/CPAGuideline_Report_JAN2011.pdf. Warburton DE, Nicol CW, Bredin SS. Health benefits of physical activity: the evidence. CMAJ. 2006 Mar 14;174(6):801-9. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.051351. PMID: 16534088; PMCID: PMC1402378.

4) Additional tips for the physician: Investigate the hospitals and institutions in which you work. Many workplaces nowadays have access to on-site facilities, equipment, and even instructor-led classes, permitting opportunities to exercise at work. If you do not have time to take a break during your clinical day, consider joining an intramural sports team that runs in the evenings, walk or bike instead of driving when possible, or take the stairs at work. Remember that every bit counts—even a 10-minute stretching exercise at work can reduce anxiety and increase energy!

1. Prioritize rest: Attaining ≥7 hours of sleep is vital. Adequate sleep is important to cognition, mood, emotional regulation, and overall physical health. While the quantity and quality of sleep can vary due to environmental disruptions, stressors, varying schedules, as well as insomnia and other sleep disorders, strategies to optimize periods of rest are reviewed below.

1) Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-i) is a strongly recommended and effective treatment, which is increasingly accessible online or via mobile apps. It provides sustained improvements in sleep.Evidence 9Strong recommendation (benefits clearly outweigh downsides; right action for all or almost all patients). High Quality of Evidence (high confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Morgenthaler T, Kramer M, Alessi C, et al; American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Practice parameters for the psychological and behavioral treatment of insomnia: an update. An American academy of sleep medicine report. Sleep. 2006 Nov;29(11):1415-9. PMID: 17162987. Schutte-Rodin S, Broch L, Buysse D, Dorsey C, Sateia M. Clinical guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic insomnia in adults. J Clin Sleep Med. 2008 Oct 15;4(5):487-504. PMID: 18853708; PMCID: PMC2576317.

2) Relaxation training is effective in managing insomnia by lowering arousal and activation of the sympathetic nervous system. Such practices include deep abdominal breathing, progressive muscle relaxation, and guided imagery.Evidence 10Strong recommendation (benefits clearly outweigh downsides; right action for all or almost all patients). Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to heterogeneity and imprecision (inability to separate different components of interventions). Morgenthaler T, Kramer M, Alessi C, et al; American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Practice parameters for the psychological and behavioral treatment of insomnia: an update. An American academy of sleep medicine report. Sleep. 2006 Nov;29(11):1415-9. PMID: 17162987. Schutte-Rodin S, Broch L, Buysse D, Dorsey C, Sateia M. Clinical guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic insomnia in adults. J Clin Sleep Med. 2008 Oct 15;4(5):487-504. PMID: 18853708; PMCID: PMC2576317.

3) Sleep hygiene can be used to improve the sleep routine and environment to foster more restful sleep. Adopting several of the recommended strategies (Table 4) may be useful, particularly if used in conjunction with other efforts such as CBT-i or relaxation training.Evidence 11Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Low Quality of Evidence (low confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to imprecision and indirectness. Morgenthaler T, Kramer M, Alessi C, et al; American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Practice parameters for the psychological and behavioral treatment of insomnia: an update. An American academy of sleep medicine report. Sleep. 2006 Nov;29(11):1415-9. PMID: 17162987. Schutte-Rodin S, Broch L, Buysse D, Dorsey C, Sateia M. Clinical guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic insomnia in adults. J Clin Sleep Med. 2008 Oct 15;4(5):487-504. PMID: 18853708; PMCID: PMC2576317.

2. Mitigate sleep debt: Sleep debt is a common occurrence for physicians, as a result of long hours, shift work, and overnight calls. It is important to not only recognize when this debt is accruing but also to repay it, so as to avoid the ill effects of sleep deprivation, including risks of making errors at work.

1) Sleep anchoring can be a useful technique for those engaging in shift work to minimize disruption to one’s circadian rhythm and regular sleep routine. Review your usual hours of sleep and try to designate 3 to 4 hours of sleep (about half of your normal sleep time) after a shift that is close to the beginning or end of your normal sleep period. Alternatively, if this seems too complicated, after an overnight shift limit your sleep to 12:00 (~4 hours or less after your call) and then opt to go to bed a few hours earlier that night.Evidence 12Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Low Quality of Evidence (low confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to limited studies, heterogeneity, and imprecision (small sample sizes). Minors DS, Waterhouse JM. Does 'anchor sleep' entrain circadian rhythms? Evidence from constant routine studies. J Physiol. 1983 Dec;345:451-67. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1983.sp014988. PMID: 6663508; PMCID: PMC1193807. Wickwire EM, Geiger-Brown J, Scharf SM, Drake CL. Shift Work and Shift Work Sleep Disorder: Clinical and Organizational Perspectives. Chest. 2017 May;151(5):1156-1172. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.12.007. Epub 2016 Dec 21. PMID: 28012806; PMCID: PMC6859247.

2) Power naps can also be a useful way to reduce fatigue and improve cognition during long shifts, where feasible to implement. Stick to naps that are about 10 to 20 minutes. This helps to avoid entering deeper sleep stages and makes them more restorative. If you must sleep longer, aim to sleep for 90 minutes, which is the duration of a full sleep cycle.Evidence 13Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Low Quality of Evidence (low confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to limited studies, heterogeneity, and imprecision (small sample sizes). Brooks A, Lack L. A brief afternoon nap following nocturnal sleep restriction: which nap duration is most recuperative? Sleep. 2006 Jun;29(6):831-40. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.6.831. PMID: 16796222.

3) Additional tips for the physician: After a call shift, try to go to sleep as soon as possible after returning home to aid with sleep anchoring. Also consider wearing sunglasses or using a sleep mask to minimize exposure to light when preparing for sleep during the daytime.

Finding Joy Outside of Medicine

Remember work-life balance: A sustainable work-life balance is often difficult to achieve in modern medicine, particularly given increased demands and technology, which permits work to be carried over into personal time. But taking time for oneself to engage in activities and relationships outside of medicine are crucial to wellness and preventing burnout.

1) Setting boundaries on one’s work can help in managing stress and also permit time to rest, relax, and refuel. This can be accomplished by setting time each day or week that is free from work-related tasks to engage in other activities that bring one joy or meaning, scheduling personal events or activities in one’s calendar, and taking postcall or vacation days that are truly work-free.Evidence 14Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Low Quality of Evidence (low confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to limited studies, often observational or commentaries. Moen P, Lam J, Ammons S, Kelly EL. Time Work by Overworked Professionals: Strategies in Response to the Stress of Higher Status. Work Occup. 2013 May 1;40(2):79-114. doi: 10.1177/0730888413481482. PMID: 24039337; PMCID: PMC3769188. Ross S, Liu EL, Rose C, Chou A, Battaglioli N. Strategies to Enhance Wellness in Emergency Medicine Residency Training Programs. Ann Emerg Med. 2017 Dec;70(6):891-897. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2017.07.007. Epub 2017 Aug 18. PMID: 28826752.

2) Engaging in hobbies and recreational or creative pursuits are recommended not only for managing stress and anxiety but to promote psychological well-being through providing joy as well as permitting relaxation and grounding. Physical activity, including sports, spiritual practices, and creative outlets such as through music, visual art, and dance are all valuable and therapeutic activities.Evidence 15Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Low Quality of Evidence (low confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to heterogeneity, inability to separate different components of interventions, and poor generalizability. Stuckey HL, Nobel J. The connection between art, healing, and public health: a review of current literature. Am J Public Health. 2010 Feb;100(2):254-63. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.156497. Epub 2009 Dec 17. PMID: 20019311; PMCID: PMC2804629. Martin L, Oepen R, Bauer K, et al. Creative Arts Interventions for Stress Management and Prevention-A Systematic Review. Behav Sci (Basel). 2018 Feb 22;8(2):28. doi: 10.3390/bs8020028. PMID: 29470435; PMCID: PMC5836011. Zazulak J, Sanaee M, Frolic A, et al. The art of medicine: arts-based training in observation and mindfulness for fostering the empathic response in medical residents. Med Humanit. 2017 Sep;43(3):192-198. doi: 10.1136/medhum-2016-011180. Epub 2017 Apr 27. PMID: 28450412.

3) Stepping out into nature has been known for centuries to be restorative for health. As time in nature often facilitates physical activity, it works to promote one’s sleep, energy, and cognitive functioning. Immersing oneself in nature also promotes mindfulness, and particularly for health-care providers it reduces stress, anxiety, and depression, as well as enhances productivity. Even just 5 to 10 minutes outside can be beneficial. If you have no time to spare, observing nature through windows, art, photos, or by caring for plants in the home also confers similar effects.Evidence 16Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Low Quality of Evidence (low confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to heterogeneity, small sample sizes, and imprecision. Hansen MM, Jones R, Tocchini K. Shinrin-Yoku (Forest Bathing) and Nature Therapy: A State-of-the-Art Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017 Jul 28;14(8):851. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14080851. PMID: 28788101; PMCID: PMC5580555. Trau D, Keenan KA, Goforth M, Large V. Nature Contacts: Employee Wellness in Healthcare. HERD. 2016 Apr;9(3):47-62. doi: 10.1177/1937586715613585. Epub 2015 Nov 17. PMID: 26578539.

Be present in the moment: Mindfulness is awareness of the present moment. It involves learning to attend to the present with intention and without judgment. There are many variations and forms of mindfulness exercises and meditations; some introductory examples: Table 5. Mindfulness is strongly recommended as an effective tool in stress management and in fostering psychological mindedness and well-being.Evidence 17Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Low Quality of Evidence (low confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to heterogeneity, performance bias, and imprecision. Ruotsalainen JH, Verbeek JH, Mariné A, Serra C. Preventing occupational stress in healthcare workers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Apr 7;2015(4):CD002892. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002892.pub5. PMID: 25847433; PMCID: PMC6718215. Hilton LG, Marshall NJ, Motala A, et al. Mindfulness meditation for workplace wellness: An evidence map. Work. 2019;63(2):205-218. doi: 10.3233/WOR-192922. PMID: 31156202; PMCID: PMC6598008.

Align work with your strengths and values: In the face of stress or adversity it is often self-criticism instead of strength and self-confidence that arises, which risks kickstarting a vicious circle of negativity. When individuals regularly use their strengths (Table 6), particularly when challenges emerge, and live in line with their core values, this is associated with overall well-being, life and job satisfaction, improvements in mental health, and greater meaning being discovered in one’s work, which can offer protection from burnout.Evidence 18Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Low Quality of Evidence (low confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to heterogeneity, small sample sizes, and inconsistency between studies. Tse S, Tsoi EW, Hamilton B, et al. Uses of strength-based interventions for people with serious mental illness: A critical review. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2016 May;62(3):281-91. doi: 10.1177/0020764015623970. Epub 2016 Feb 1. PMID: 26831826.

Write for the soul: Various forms of writing exist (Table 7), and many of these foster emotional expression and cognitive processing, which can be beneficial for health and well-being. In times of stress it can be a useful tool to lessen distress and depressive symptoms, strengthen adaptive coping skills and social supports, and promote empathy.Evidence 19Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Low Quality of Evidence (low confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to heterogeneity and imprecision (inability to separate different components of interventions). Chen I, Forbes C. Reflective writing and its impact on empathy in medical education: systematic review. J Educ Eval Health Prof. 2014 Aug 16;11:20. doi: 10.3352/jeehp.2014.11.20. PMID: 25112448; PMCID: PMC4309942. Davis DE, Choe E, Meyers J, et al. Thankful for the little things: A meta-analysis of gratitude interventions. J Couns Psychol. 2016 Jan;63(1):20-31. doi: 10.1037/cou0000107. Epub 2015 Nov 16. PMID: 26575348. Ullrich PM, Lutgendorf SK. Journaling about stressful events: effects of cognitive processing and emotional expression. Ann Behav Med. 2002 Summer;24(3):244-50. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2403_10. PMID: 12173682.

Cultivate Connectedness and Compassion

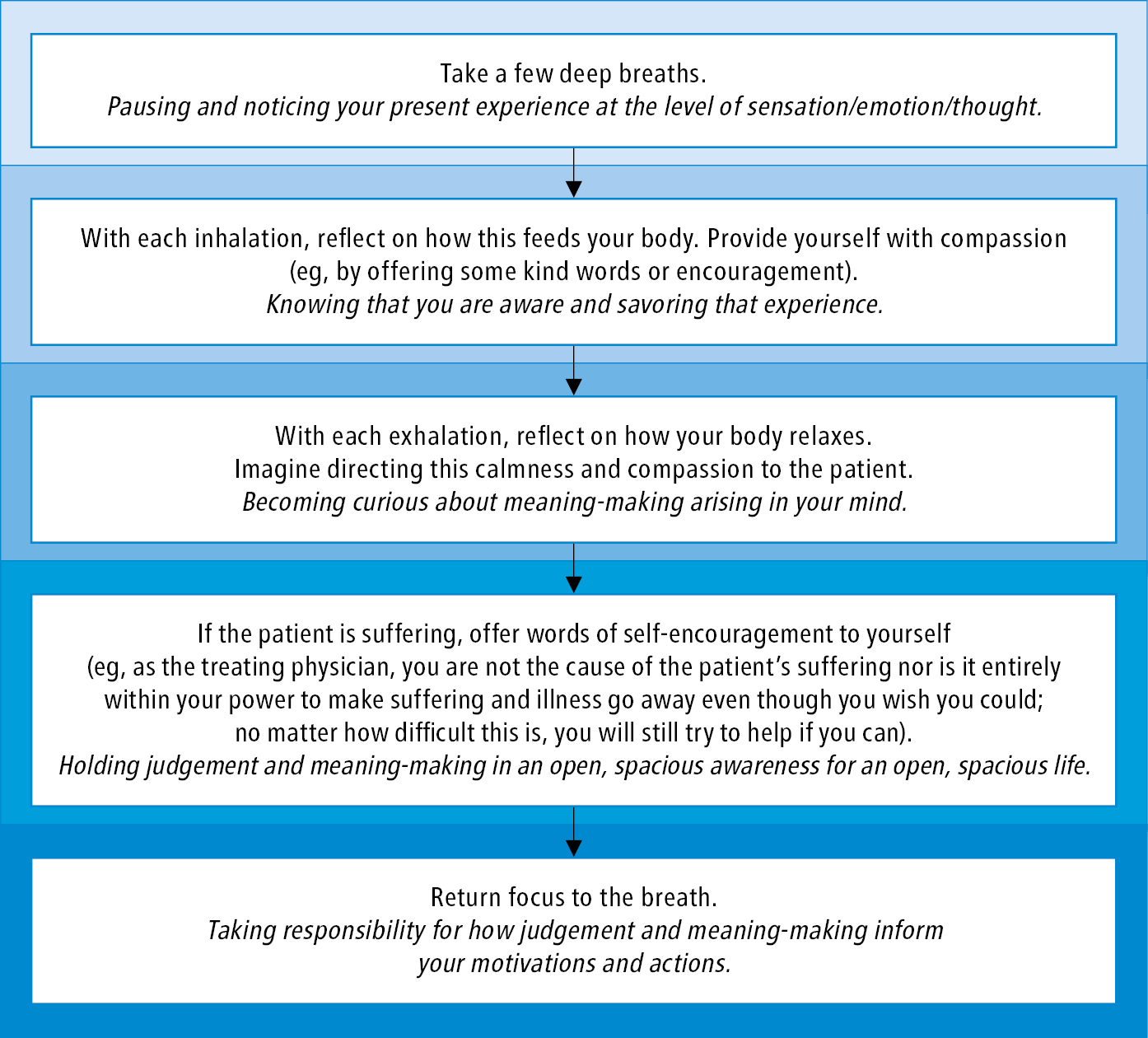

Be kind to yourself everyday: True self-compassion integrates 3 components: mindfulness, self-kindness, and common humanity. When used together in daily practices, they allow one to reflect and process emotions and struggles—particularly those common to medical training and practice—with warmth and understanding instead of judgment as well as serve as a reminder that we are not alone, that suffering and failure are part of a shared human experience. Fostering self-compassion can reduce rates of psychopathology (ie, depression, anxiety) and increase psychological well-being and life satisfaction. Simple self-compassion practices: Table 8, Figure 4, Figure 5.Evidence 20Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Low Quality of Evidence (low confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to heterogeneity, performance bias, and imprecision. MacBeth A, Gumley A. Exploring compassion: a meta-analysis of the association between self-compassion and psychopathology. Clin Psychol Rev. 2012 Aug;32(6):545-52. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.06.003. Epub 2012 Jun 23. PMID: 22796446. Zessin U, Dickhäuser O, Garbade S. The Relationship Between Self-Compassion and Well-Being: A Meta-Analysis. Appl Psychol Health Well Being. 2015 Nov;7(3):340-64. doi: 10.1111/aphw.12051. Epub 2015 Aug 26. PMID: 26311196.

Engaging Social Support Systems

1. Connect with your peers: Human connection, which fosters a sense of belonging and support, is a vital component of resilience and well-being. Connecting with others, whether this be friends, family, or colleagues, is a chief coping strategy among medical trainees and physicians. While informal meetups have a protective effect against burnout for physicians, offering a chance to discuss experiences, vent or rant, or simply laugh and be together, more formal forms of peer support can also be effective.

Near-peer mentorship, connecting junior and senior medical learners or physicians across different stages of practice, offers the opportunity to regularly meet with someone with similar lived experience and understanding of the unique experiences facing those of us in medicine without fear of reprisal. Mentorship promotes personal and professional development (ie, collegiality, professionalism, confidence), reduces stress, and helps develop resilience.Evidence 21Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Low Quality of Evidence (low confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to heterogeneity and imprecision. Akinla O, Hagan P, Atiomo W. A systematic review of the literature describing the outcomes of near-peer mentoring programs for first year medical students. BMC Med Educ. 2018 May 8;18(1):98. doi: 10.1186/s12909-018-1195-1. Erratum in: BMC Med Educ. 2018 Jul 13;18(1):167. PMID: 29739376; PMCID: PMC5941612. Peterson U, Bergström G, Samuelsson M, Asberg M, Nygren A. Reflecting peer-support groups in the prevention of stress and burnout: randomized controlled trial. J Adv Nurs. 2008 Sep;63(5):506-16. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04743.x. PMID: 18727753. Pethrick H, Nowell L, Oddone Paolucci E, et al. Psychosocial and career outcomes of peer mentorship in medical resident education: a systematic review protocol. Syst Rev. 2017 Aug 31;6(1):178. doi: 10.1186/s13643-017-0571-y. PMID: 28859683; PMCID: PMC5579942.

2. Form physician groups: Many physicians and medical trainees often suffer in silence, believing they are alone in their struggles and fearing being vulnerable or open about their discomfort, stressors, and adverse outcomes, given the demanding and rigid culture in which they are immersed. Building a community and fostering a sense of belonging is meaningful and effective not only in mitigating burnout but also in providing avenues for needed support. To date, there are several forms of physician groups and rounds that can be beneficial:

1) Balint groups are structured reflective groups for physicians to engage in affective processing around difficult clinical and workplace encounters. Such groups are used to prevent burnout by increasing a physician’s capacity to cope with the stresses of medicine, fostering empathy, and lessening perceived isolation.Evidence 22Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Low Quality of Evidence (low confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to heterogeneity, risk of bias, and imprecision. Monk A, Hind D, Crimlisk H. Balint groups in undergraduate medical education: a systematic review. Psychoanal Psychother. 2018;32(1):61-86. doi: 10.1080/02668734.2017.1405361. Yazdankhahfard M, Haghani F, Omid A. The Balint group and its application in medical education: A systematic review. J Educ Health Promot. 2019 Jun 27;8:124. doi: 10.4103/jehp.jehp_423_18. PMID: 31334276; PMCID: PMC6615135.

2) Doctoring to Heal groups, which can also take the form of informal groups such as Ice Cream Rounds, are regular discussion groups among medical learners or physicians in which a topic pertaining to work as a health-care provider is explored in an open forum. Examples of topics include medical errors, adverse events and patient loss, feedback and failure, work-life balance, and seeking help for personal burnout or struggles. By sharing reflections, experiences, and personal narratives, physicians can individually develop meaning in medicine, process difficult experiences and emotions, and collectively be immersed within a supportive community where they can learn from one another. Such groups can promote the well-being of physicians by lessening isolation, strengthening one’s identity and meaning in medicine, and sharing of supports.Evidence 23Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Low Quality of Evidence (low confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to heterogeneity and imprecision. Calder-Sprackman S, Kumar T, Gerin-Lajoie C, Kilvert M, Sampsel K. Ice cream rounds: The adaptation, implementation, and evaluation of a peer-support wellness rounds in an emergency medicine resident training program. CJEM. 2018 Sep;20(5):777-780. doi: 10.1017/cem.2018.381. Epub 2018 May 30. PMID: 29843841. Rabow MW, McPhee SJ. Doctoring to Heal: fostering well-being among physicians through personal reflection. West J Med. 2001 Jan;174(1):66-9. doi: 10.1136/ewjm.174.1.66. PMID: 11154679; PMCID: PMC1157069.

3) Gratitude Rounds are useful in promoting collegiality and connectedness as well as improving meaning in medicine by reflecting on the joys of medicine. Physicians and trainees meet regularly for 30 to 60 minutes to share satisfying or meaningful clinical encounters, remind one another of the aspects of medicine they enjoy and are passionate about, and acknowledge colleagues and systems that have been supportive.

3. Debrief after an adverse event or difficult encounter: Certain clinical situations, such as a difficult code, patient death, violence by patients or family members, or medical errors, can cause significant distress for physicians, which can fester if left unprocessed. Debriefing has been shown to be therapeutic, whether informally with another provider or colleague or formally through structured team debriefing or regular “grief rounds” to reflect on these experiences. Debriefing can provide needed support and adaptive processing of these experiences as well as prevent harmful internalization that would otherwise lead to feelings of failure and self-blame.Evidence 24Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Low Quality of Evidence (low confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to heterogeneity and inconsistency between studies. Everly GS Jr, Boyle SH. Critical incident stress debriefing (CISD): a meta-analysis. Int J Emerg Ment Health. 1999 Summer;1(3):165-8. PMID: 11232385. Wilde L, Worster B, Oxman D. Monthly "Grief Rounds" to Improve Residents' Experience and Decrease Burnout in a Medical Intensive Care Unit Rotation. Am J Med Qual. 2016 Jul;31(4):379. doi: 10.1177/1062860616652063. Epub 2016 May 23. PMID: 27259873.

The Stanford WellMD Professional Fulfillment Model outlines 3 key domains of professional fulfillment and well-being: personal resilience, efficiency of practice, and culture of wellness. While personal resilience may in part be the responsibility of the individual physician, medical systems and organizations have a substantial and important role in bringing about change within all these domains as well as in providing accessible pathways to skills, resources, and formal care.

While there may be several suggestions for system-level change and support to supplement and advance personal coping strategies (Table 9), it is important to recognize that there is no one size that fits all. The most effective and sustainable solutions will be those that best meet the needs of providers, which may vary over time and by institution or system. The American Hospital Association has developed a framework (Table 10) to guide organizations and institutions in transforming their system to one that promotes well-being. This framework, with many aspects also supported by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, has been successfully used by a variety of health-care facilities to date, with benefits including increased physician engagement, recruitment, and retention; strengthened physician communities; and improvement of factors contributing to burnout and stress.

Staying Well During Public Health OutbreaksTop

The COVID-19 pandemic launched our generation into unprecedented times. Placing unchartered demands on our health-care facilities and economy, requiring unimaginable social distancing efforts, and resulting in immense societal fear, uncertainty, anxiety, and stress that—while normal during this time—will likely linger long after the peak of this crisis.

For physicians and health-care providers working at the front lines, there are additional stresses and worries that exemplify the mix of emotions at this time. Fears of exposing families and patients to the novel coronavirus, lack of access to personal protective equipment, juggling work with family duties, increased workloads, exposure to catastrophic illness and death rates, and immense grief of losing patients and loved ones are just a few examples.

Fortunately, there is a variety of strategies and approaches to mitigate stress during global public health crises, which help to maintain our physical and psychological well-being, so that we can continue functioning at our best to care for our families and our communities. A few high-yield practical tips to stay well during the current COVID-19 pandemic: Figure 6.

During global public health crises, physicians and health-care providers are increasingly being relied upon to provide support and guidance to friends, family members, and patients alike. A simple approach to being present for others and offering support during the difficult time of COVID-19: Figure 7.

Formal ResourcesTop

As a supplement to the material in this chapter, there are several additional self-help resources, which may further one’s knowledge of physician burnout and resilience, in addition to advancing coping skills and supports. A curated list of recommended readings and websites, many of which were used in the development of this chapter: Table 11.

There are times during one’s medical training and career when the support one requires goes beyond that which can be provided by the individual themselves or through engagement in less intensive resources and tools, such as those covered earlier in this chapter. Checking in with oneself and attuning to one’s own struggles and needs can help in recognizing when it may be time to ask for help and seek more formal support. This may include accessing one’s program director, department lead, or chief of service; a primary care physician; mental health and counseling services; or other crisis services, including a local emergency department if one is in need of immediate support. A list of supports for medical learners and physicians specific to McMaster University: Table 12, Table 13; those at other sites may wish to explore what similar resources exist within their programs and institutions.

Tables and FiguresTop

|

Emotional exhaustion |

Depersonalization |

Reduced sense of self-efficacy |

|

– Fatigue – Dread – Disrupted sleep – Impaired focus – Somatic symptoms (eg, headache, gastrointestinal upset, muscle tension, increased illness) |

– Negativity – Cynicism – Anger or irritability – Detachment or apathy – Isolation |

– Self-doubt – Reduced self-esteem – Feelings of failure – Reduced productivity and engagement at work – Lost value, satisfaction, and meaning in work |

|

Individual |

Practice |

Organization/system |

|

– Female sex – Younger age – Partner in a nonmedical profession – Children or dependents aged <21 years |

– Front-line specialties – Private practice – Performance-based compensation – Heavy workloads – Frequent exposure to suffering and trauma |

– System inefficiencies – Documentation – Lack of autonomy – Lack of resources – Poor leadership – Hidden curriculum |

|

Criterion A symptoms: (1) delusions; (2) hallucinations; (3) disorganized speech; (4) disorganized or catatonic behavior; (5) negative symptom |

|

Schizophrenia: – ≥2 criterion A symptoms present; ≥1 must be (1), (2), or (3) – Duration of acute phase: ≥1 month (or <1 month if successfully treated) – Duration of illness: ≥6 months – Specifier: First episode, currently in acute episode/partial remission/full remission; multiple episodes, currently in acute episode/partial remission/full remission; continuous; unspecified |

|

Schizoaffective disorder: – Criterion A (1) or (2) symptom present for ≥2 weeks in the absence of a major mood episode during the lifetime duration of illness – Criterion A (as above) concurrent with a major mood episode (depressive or manic); a major mood episode present for the majority of the total duration of active and residual portions of illness – Specifier: Bipolar type, depressive type |

|

Schizophreniform disorder: – ≥2 criterion A symptoms present; ≥1 must be (1), (2), or (3) – Duration of acute phase: ≥1 month – Duration of illness: <6 months – Specifier: With/without good prognostic features |

|

Brief psychotic disorder: – ≥1 of criterion A symptoms (1), (2), (3), or (4) – ≥1 must be (1), (2), or (3) – Duration: ≤1 month; full resolution of symptoms and return to premorbid functioning level – Specifier: With/without marked stressor(s), with postpartum onset |

|

Delusional disorder: – ≥1 delusion – Other criterion A symptoms not met (if present, hallucinations are not prominent and related to delusional theme) – If present, manic or major depressive episodes are brief relative to the duration of illness – Duration of illness: ≥1 month – Specifier: Erotomanic type, grandiose type, jealous type, persecutory type, somatic type, mixed type |

|

Substance/medication-induced psychotic disorder: – ≥1 of criterion A symptoms (1) or (2) – Criterion A symptoms occur during or soon after substance intoxication or withdrawal or after exposure to medication – Substance/medication is capable of producing criterion A symptoms; not occurring exclusively during delirium – Specifier: With onset during intoxication, with onset during withdrawal |

|

DSM-5, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fifth Edition). |

|

– Ensure the bedroom is comfortable, quiet, and dark. – Avoid using the bed for activities other than sleep and sex. – Set a routine: go to bed and awaken at the same time each day. – Regular physical activity can be helpful, but avoid strenuous exercise right before sleep. – Avoid eating a heavy meal or drinking too many liquids within 90 minutes of bedtime. – Avoid using alcohol, caffeine, and nicotine prior to sleep. – Avoid stimulating activities, such as screen time, at least 30 minutes prior to sleep. Instead opt for quiet, relaxing activities, such as reading, meditating, progressive muscle relaxation, or listening to soft music. |

|

Technique |

Description |

|

Breath awareness |

Simply take a few moments to observe the inhalations and exhalations of one’s breath. This serves as a meditative anchor in the practice and works to ground oneself in the present and regulate one’s emotions. |

|

Observe the mind |

While many consider the idea of mindfulness to be “quieting of the mind,” it is natural for thoughts to come and go and for our minds to drift. In these moments, being an observer means simply noting the thought, without judgment, and returning to the present moment, such as to one’s breath. If this is difficult, imagine placing each thought on an imaginary leaf that one then places on a stream from which it drifts away. This permits acknowledgement of the thought, again without judgment and without self-criticism and painful emotions. |

|

Incorporate the practice into any moment |

While there are many mindfulness meditative practices in existence, many of which can be accessed online or through apps, mindfulness can easily be integrated into our daily routine. Even with the most mundane or simple of activities (eg, brushing teeth, having a shower, eating, walking, listening to music), take a few moments to connect with your senses, savoring the experience. |

|

1. Identify your top 5 core strengths, those that you would consider central to your identity. If you encounter difficulties with this, consider reflecting on what a friend, family member, or colleague might say about your strengths. There are several free online surveys to assess this, such as the VIA Character Strengths Survey. |

|

2. Utilizing at least 4 of your core strengths in your work can be beneficial. Reflect on how these strengths are currently being used. Is there an opportunity to capitalize on your strengths or further incorporate these into your work and activities? Reflect on how these strengths may have helped you overcome challenges or struggles in the past. Consider how your strengths may help you to work through or cope with a current stressor or challenges in the future. |

|

Technique |

Description |

|

Reflective writing |

This involves simply documenting an event that occurred and sharing the emotional reactions that arose as a result. The practice often provides a safe space not only to release the emotions attached to the event but to reflect on both the positives and negatives of the experience, which helps to construct a more meaningful narrative. |

|

Gratitude journaling |

A well-studied practice that involves regular recording of 3-5 items or experiences that one is grateful/thankful for and appreciative/proud of. Positive effects, including reduced risk of mental health problems (eg, burnout) as well as increased resilience, happiness, and self-acceptance, are noted even with journaling for 15 minutes just 1-2 times per week. |

|

Compassionate journaling |

Enhances the benefits of reflective writing through integrating self-compassion (explored further in this chapter). The first step is reflecting on a situation that is weighing on one’s mind and exploring the emotions and factors involved without judgment. This is followed by acknowledging that others may have had similar experiences or that this experience may reflect being human, and then offering some kindness and understanding to the self (whether by using one’s own voice or that of a loved one or friend). |

|

Compassionate letter writing |

While similar to compassionate journaling, letter writing tends to focus more on a perceived flaw or inadequacy that may provoke shame or deeper pain. Individuals reflect on this with kindness, considering what a trusted or loved one would say about this trait, how others may share in the same struggle, and offer warm words to help cope with this or provide feedback to support further growth. |

|

Exercise |

Description |

|

Daily self-compassion |

This practice can be used at any time but is often most effective when feeling stressed, tired, or burned out. It provides physicians with permission both to acknowledge their own stress as well as to respond by addressing their own needs and taking care of themselves. How to: 1) Recognize when you are feeling stressed or overwhelmed. 2) Reflect on what it is you need during this time. 3) Respond by addressing this need and/or engaging in self-care or an activity that calms, comforts, or provides pleasure. |

|

Using sense of touch through self-soothing |

This practice serves as a reminder to be warm and kind to oneself, particularly when feeling down or struggling with trauma and suffering that physicians commonly witness. How to: 1) Adopt a soothing touch position. Placing a hand over the heart is common, but find a position that is comfortable for you. 2) Observe the sensations in your hand or body in this position. Take notice of your breath, which nourishes you when inhaling and releases tension when exhaling. 3) Continue simply noticing these sensations for a few moments. |

|

Giving and receiving compassion |

It is not uncommon for physicians to experience empathic fatigue as they repeatedly bear others’ suffering. Compassion can be a powerful antidote; however, to be effective, it needs to be provided to both the physician and the patient. Providing compassion to oneself as a health-care provider builds one’s capacity to attune to another’s suffering and provide support. Further, compassion in such situations maintains well-being, as well as fosters emotional resonance, in which two individuals are able to connect deeper emotionally. How to: Figure 4. |

|

Reflect compassionately on work and experiences |

Physicians are often highly self-critical, frequently fixating on perceived failures or inadequacies. This can perpetuate a cycle of anxiety, self-doubt, negative affect and self-esteem, and loss of meaning and satisfaction in one’s work. While it may be important to reflect on our work, particularly errors and failures, which offer valuable learning moments, it is also equally important to do so from a balanced and kind perspective. How to: Figure 5. |

|

Individual resilience strategy |

Ideas for how to expand systemically to bring about greater and more sustainable change |

|

Attend to basic needs |

– Standardized break times to hydrate and refuel – Increased cafeteria and vendor hours, access to healthier food choices – On-site access to exercise space and equipment – Formal wellness programs, which may include teaching on health and fitness and breaks to engage in exercise – Duty hour/overnight hour restrictions, where feasible – Ability to split shifts with colleagues – Protected downtime before calls to rest – Blackout periods on overnight calls – Use of physician extenders for overnight duties |

|

Break away from stress |

– Increased recognition and rewarding of efforts – Flexibility to adapt practice and schedule to personal needs, interests, and fit – Access to confidential formal supports and care – Formalized wellness curriculum in medical training and residency to teach how to address stress in medicine – Modeling of adaptive coping strategies by leaders |

|

Cultivate connectedness and compassion |

– Access to and protected time for learners and staff to engage in peer support or structured groups and rounds – Normalized debriefing after a critical incident or adverse event – Support training of health-care providers to serve as group facilitators or peer mentors – Comfortable and private common rooms or break areas for learners and physicians – Increased team-building exercises and social events – Greater use of team-based models of care, recognition of effective teamwork |

|

Action |

Description |

|

Build infrastructure |

For change to be sustainable, there must be infrastructure to support it. Advocate for organizational structures to match values and ensure there is commitment from leadership and resources to support wellness efforts and initiatives. |

|

Engage a wellness team |

Identify a wellness leader or officer and appoint a wellness team, ideally composed of all organizational stakeholders, including clinician representatives. |

|

Assess and measure needs and well-being |

Conduct a needs assessment. This should include measures of general clinician well-being, which will help to assess the impact of interventions in the future, as well as explore the current factors and barriers to wellness, which will direct interventions. |

|

Design interventions |

Plan and develop initiatives or solutions to address factors or issues that provoke the greatest stress among clinicians. |

|

Implement pilot initiatives/programs |

Take care to plan, prepare, and implement new programs. Ensure these are well communicated to all staff. |

|

Evaluate program impact and success |

Obtain feedback from clinicians regarding the pilot intervention. Consider surveys to evaluate the uptake, effectiveness, and overall satisfaction with the program. |

|

Shift to a more sustainable culture |

– This requires continual review, assessment, learning, and program development. – Keep staff and clinicians engaged, and design reward and recognition systems. |

|

Resource |

Description |

|

Books and readings | |

|

Attending: Medicine, Mindfulness, and Humanity by Ronald Epstein |

Written by an expert physician combining his own clinical and personal experiences with current research, this is a useful introductory book that highlights the utility of mindfulness in medical practice. |

|

Humanism and Resilience in Residency Training: A Guide to Physician Wellness by Ana Hategan, Karen Saperson, Sheila Harms, and Heather Waters (editors) |

A concise evidence-based guide for medical learners and physicians, which provides tools and approaches to enhance individual resilience and foster humanism in medicine. |

|

Taking Action Against Clinician Burnout: A Systems Approach to Professional Well-Being by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine |

A thorough resource using up-to-date research and data regarding health-care provider burnout, related implications, and contributing factors. This book also provides a framework from which to systemically approach clinician and health-care provider wellness. |

|

The Mindful Self-Compassion Workbook by Kristin Neff and Christopher Germer |

A user-friendly workbook, which builds knowledge of the science and practicalities of mindful self-compassion as well as fosters skill development through sharing of a variety of practices and exercises. |

|

Online resources and websites | |

|

Self-Compassion at self-compassion.org |

A comprehensive website developed by Kristin Neff, a cofounder of mindful self-compassion, providing readings, research, as well as guided self-compassion meditations and exercises for the beginner. |

|

Resilience in the Era of Sustainable Physicians: An International Training Endeavour (RESPITE) at respite.machealth.ca |

A free online resilience curriculum for physicians and medical trainees designed to expand one’s knowledge and learn strategies to enhance individual wellness and mitigate the effects of burnout. |

|

Support |

Description and how to access |

|

McMaster Student Wellness Centre |

– Available to full-time undergraduate students (including undergraduate medical students) as well as full-time and part-time graduate students at McMaster – Providing a variety of services, including health and wellness education and prevention programs, medical care with access to psychiatry and naturopathic medicine, and counseling – Call 905-525-9140 ext 27700, email wellness@mcmaster.ca, or visit wellness.mcmaster.ca |

|

Student Affairs at McMaster University |

– Available to McMaster undergraduate medical students – Providing individual counseling, career planning, mentorship and peer support, as well as sessions to promote wellness |

|

Resident Affairs at McMaster University |

– Available to McMaster resident physicians and fellows – Providing individual counseling as well as educational sessions related to wellness and financial health |

|

Professional Association of Residents of Ontario (PARO) |

– Available to medical students, residents, and their partners and families – Confidential helpline providing support and resources for various matters including stress, depression, substance use, abuse or trauma, mistreatment, and career-related crises – Call 1-866-HELP-DOC or visit www.myparo.ca |

|

Ontario Medical Association’s Physician Health Program (PHP) |

– Available to medical students, residents, physicians, and their families – Offering workshops and presentations to promote resilience and wellness as well as providing confidential support for a variety of concerns that may impact a physician personally or professionally, including mental health issues; referrals can also be made to local clinicians and health-care providers for counseling or further treatment – Call 1-800-851-6606 or email pho@oma.org |

|

Canadian Medical Association (CMA) |

– Available to medical students, residents, physicians, and their families – 24/7 support line for counseling and mental health supports; visit www.cma.ca/supportline/ – Offering The Wellness Connection, a virtual safe space for medical trainees and physicians to express and share gratitude as well as provide and receive support by participating in various facilitated peer groups; visit community.cma.ca/en/wellness-connection |

|

Canadian Medical Protective Association (CMPA) |

– Available to medical graduates who are licensed or registered with a Canadian regulatory body or college – Providing confidential medical-legal support and assistance – Call 1-800-267-6522 or visit www.cmpa-acpm.ca |

|

Crisis line |

Description and how to access |

|

Kids Help Phone |

– 24/7 national helpline for children and youth in Canada – Providing confidential support, counseling, referrals, or additional resources for youth to promote well-being and help address mental health issues or crises – Call 1-800-668-6868, text “HOME” to 686868, or visit kidshelpphone.ca |

|

Good2Talk |

– 24/7 helpline for post-secondary students in Ontario – Providing professional information, support, counseling, and referrals for mental health, addiction, and general well-being – Call 1-866-925-5454, text “GOOD2TALKON” to 686868, or visit good2talk.ca |

|

Barrett Centre for Crisis Support |

– 24/7 helpline accessible to all residents of the city of Hamilton – In addition to the helpline also offering in-person crisis counseling as well as a short-term stay for crisis support and stabilization – Call 905-529-7878 or visit www.goodshepherdcentres.ca |

|

Crisis Outreach and Support Team (COAST) |

– 24/7 helpline accessible to all residents of the city of Hamilton – Providing crisis support and follow-up as well as running a mobile outreach team – Call 905-972-8338 or 1-844-972-8338 or visit coasthamilton.ca |

Figure 16.17-1. A multifactorial lens to understanding the causes of physician burnout.

Figure 16.17-2. Consequences of physician burnout.

Figure 16.17-3. The “ABCS” of managing physician stress and burnout.

Figure 16.17-4. Exercise on how to navigate from mindfulness and self-compassion toward equanimity. This is a useful practice for health-care providers who may find themselves in caregiving situations that can be overwhelming, exhausting, or stressful. In difficult encounters this practice promotes adaptive coping with one’s emotions as well as appropriately recognizing what may or may not be in our power to change.

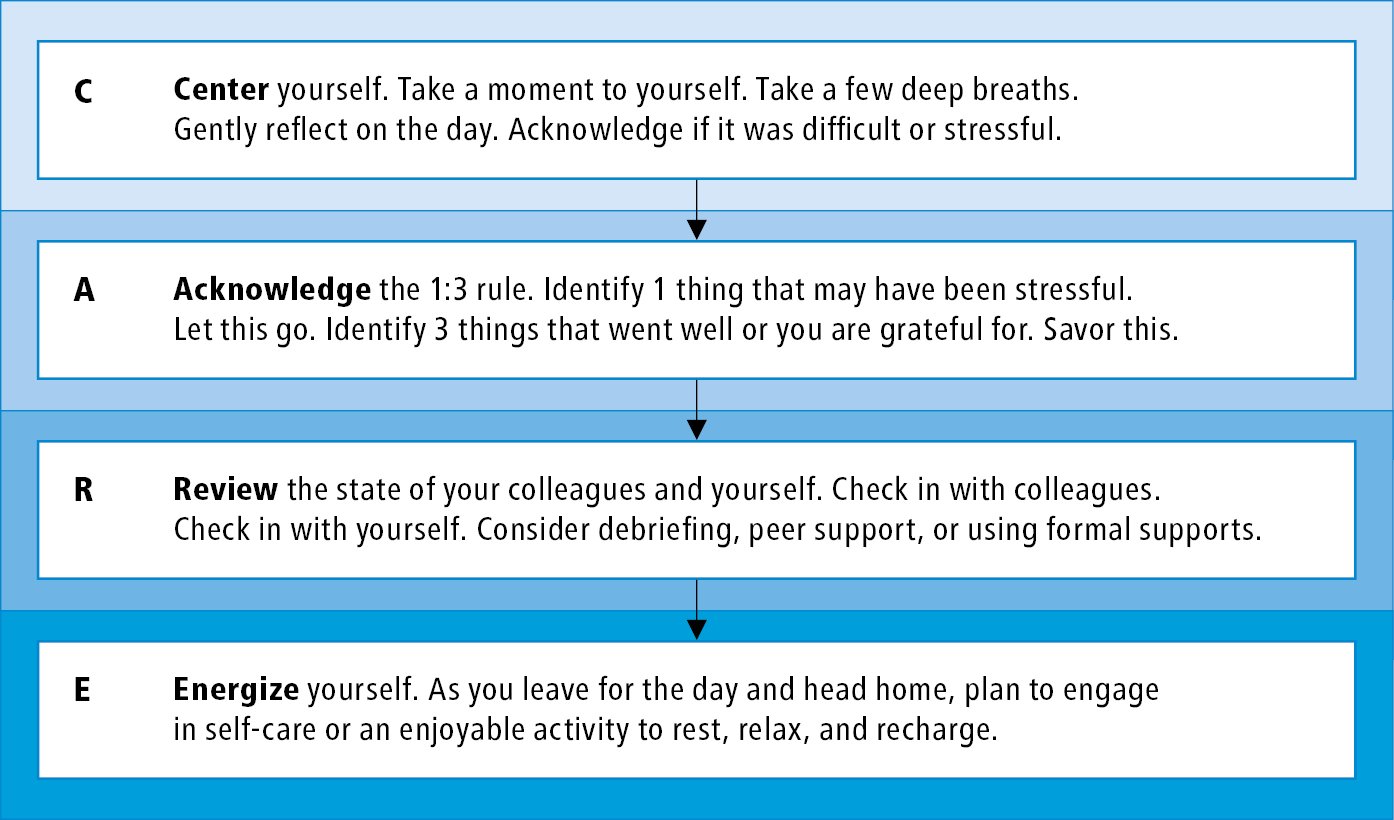

Figure 16.17-5. Compassionate acceptance and reflection of our efforts (CARE). Developed by the authors of this chapter, CARE is a 4-step activity that can be used at the end of one’s shift or day. Though it has not been studied itself, it is founded upon self-compassion and positive psychology literature as well as that around debriefing and social support. It can aid with processing and reframing negative thoughts as well as promoting gratitude and one’s mood.

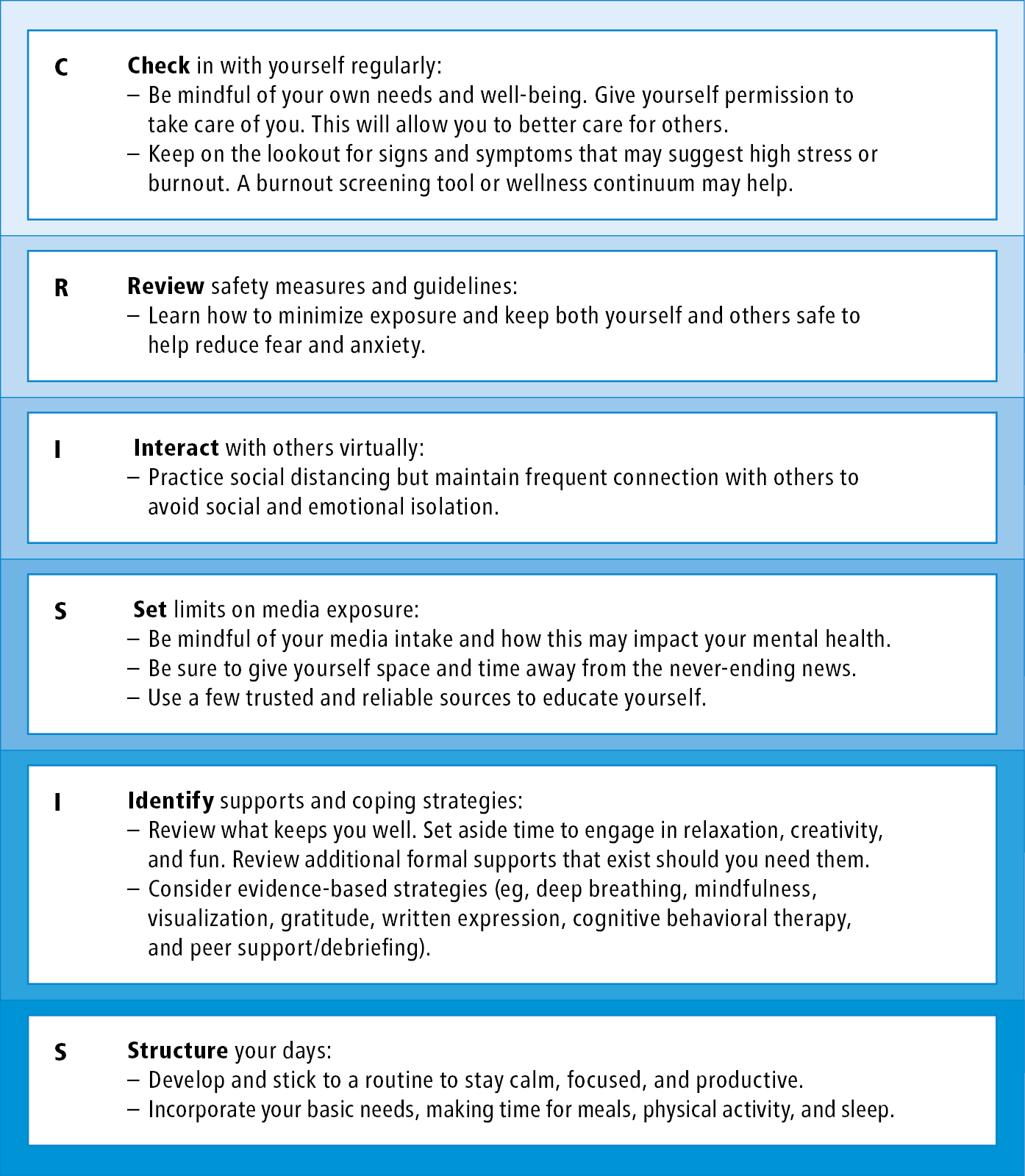

Figure 16.17-6. The CRISIS approach to managing coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)-related stress and anxiety for health-care providers.

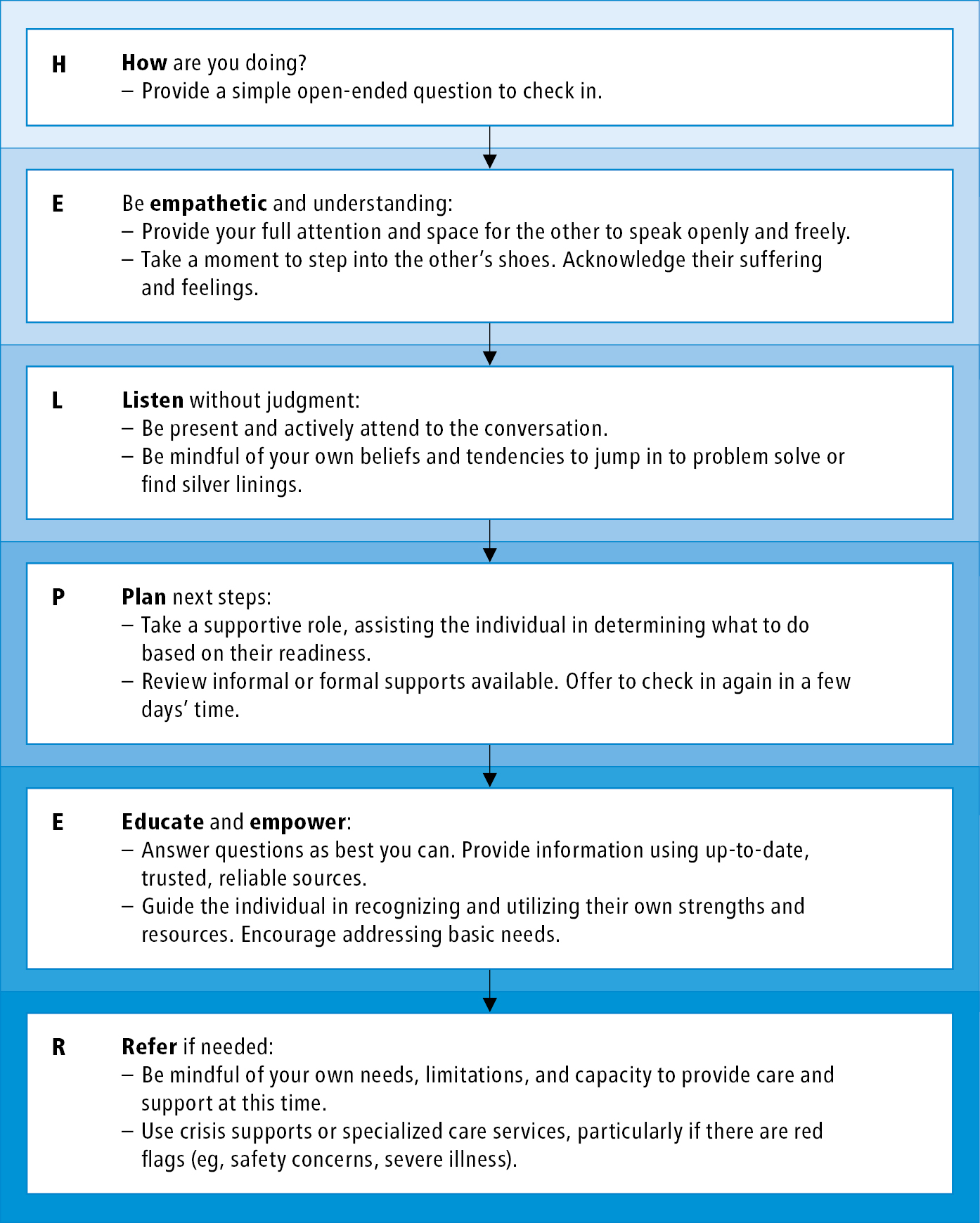

Figure 16.17-7. The HELPER approach to supporting patients, colleagues, and loved ones during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.