Stevens SM, Woller SC, Kreuziger LB, et al. Antithrombotic Therapy for VTE Disease: Second Update of the CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. Chest. 2021 Dec;160(6):e545-e608. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2021.07.055. Epub 2021 Aug 2. Erratum in: Chest. 2022 Jul;162(1):269. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2022.05.028. PMID: 34352278.

Martin KA, Beyer-Westendorf J, Davidson BL, Huisman MV, Sandset PM, Moll S. Use of direct oral anticoagulants in patients with obesity for treatment and prevention of venous thromboembolism: Updated communication from the ISTH SSC Subcommittee on Control of Anticoagulation. J Thromb Haemost. 2021 Aug;19(8):1874-1882. doi: 10.1111/jth.15358. Epub 2021 Jul 14. PMID: 34259389.

Kearon C, de Wit K, Parpia S, et al; PEGeD Study Investigators. Diagnosis of Pulmonary Embolism with d-Dimer Adjusted to Clinical Probability. N Engl J Med. 2019 Nov 28;381(22):2125-2134. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1909159. PMID: 31774957.

Konstantinides SV, Meyer G, Becattini C, et al; The Task Force for the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). 2019 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism developed in collaboration with the European Respiratory Society (ERS): The Task Force for the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Respir J. 2019 Oct 9;54(3):1901647. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01647-2019. PMID: 31473594.

Farge D, Frere C, Connors JM, et al; International Initiative on Thrombosis and Cancer (ITAC) advisory panel. 2019 international clinical practice guidelines for the treatment and prophylaxis of venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2019 Oct;20(10):e566-e581. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30336-5. Epub 2019 Sep 3. PMID: 31492632.

Lim W, Le Gal G, Bates SM, et al. American Society of Hematology 2018 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: diagnosis of venous thromboembolism. Blood Adv. 2018 Nov 27;2(22):3226-3256. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2018024828. PMID: 30482764; PMCID: PMC6258916.

Kearon C, Akl EA, Ornelas J, et al. Antithrombotic Therapy for VTE Disease: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. Chest. 2016 Feb;149(2):315-352. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2015.11.026. Epub 2016 Jan 7. Erratum in: Chest. 2016 Oct;150(4):988. PMID: 26867832.

Zawilska K, Bała MM, Błędowski P, et al; Working Group from the Anticoagulation and Thrombolytic ACCP Conference. [Polish guidelines for the prevention and treatment of venous thromboembolism. 2012 update]. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2012;122 Suppl 2:3-74. Polish. PMID: 23385605.

Definition, Etiology, PathogenesisTop

Pulmonary embolism (PE) refers to the occlusion of the pulmonary artery or some of its branches by an embolus. The embolus may be formed by thrombi (the most frequent cause of PE; these usually originate from deep veins of the lower extremities or the pelvis, less commonly from veins of the upper parts of the body; this type of PE is a clinical manifestation of deep vein thrombosis [DVT]), or occasionally by amniotic fluid, air (during insertion or removal of a central venous catheter), fat (after a long bone fracture), tumor cells (eg, renal cancer, right-sided myxoma), septic emboli (including right-sided endocarditis), or a foreign body (eg, material used for embolization procedures).

Risk factors for PE are the same as in the case of DVT (see Deep Vein Thrombosis). In approximately half of all cases no risk factors are identified (idiopathic PE).

Complications of PE (severity depends on the embolus size and individual cardiovascular reserve):

1) Ventilation-perfusion mismatch leading to impairment of gas exchange and subsequent hypoxemia (it may be aggravated by shunt of poorly oxygenated blood from the right to the left atrium via a patent foramen ovale).

2) An increase in pulmonary vascular resistance (aggravated by vasoconstriction due to hypoxemia) results in increased right ventricular afterload, right ventricular dilation, decreased left ventricular filling, reduction in cardiac output, hypotension/shock, and impaired coronary blood flow, eventually leading to acute ischemia and injury to the overloaded right ventricle. Impairment of coronary blood flow may cause myocardial injury or even a transmural myocardial infarction with normal coronary arteries, and irreversible progressive right ventricular failure is one of the major causes of death. In patients with heart failure (HF) occlusion of even a small proportion of the pulmonary artery branches may result in shock, whereas in young and otherwise healthy individuals substantial occlusion of the pulmonary vascular bed may cause only minor clinical symptoms. Emboli in the peripheral branches of the pulmonary arteries may lead to lung infarcts and focal atelectasis. An increase in right atrial pressure may cause opening of the foramen ovale (this is anatomically patent in approximately a third of the healthy population), thus allowing a venous thrombus to pass and embolize into the systemic circulation (paradoxical embolism). After hemodynamic stabilization, gradual recanalization of the pulmonary arteries takes place; in rare cases, the emboli do not dissolve despite adequate treatment and slowly undergo organization, which may lead to the development of chronic pulmonary hypertension.

Clinical Features and Natural HistoryTop

1. Symptoms often have a sudden onset and include dyspnea (in ~80% of patients), chest pain (~50%; usually with features of pleural pain, less commonly resembling coronary pain [10%]), cough (20%, usually dry), less frequently collapse or syncope and hemoptysis.

2. Signs: More than half of patients develop tachypnea and tachycardia. In the case of right ventricular dysfunction signs include dilation of the jugular veins, a loud pulmonary component of the second heart sound and/or right ventricular third heart sound, sometimes a tricuspid regurgitation murmur, hypotension, and signs of shock. Pleural friction rub may develop with peripheral lung infarction.

3. Natural history: Symptoms of DVT occur in approximately one-fourth of patients. Mortality in untreated PE depends on the clinical severity of the disease (see Diagnostic Workup, below) and is up to 30%.

DiagnosisTop

1. Blood tests: Increased serum D-dimer levels. In the majority of patients with high-risk or intermediate-risk PE, elevated levels of cardiac troponins, natriuretic peptides (B-type natriuretic peptide [BNP] or N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide [NT-proBNP]), or both are seen, which is indicative of right ventricular overload.

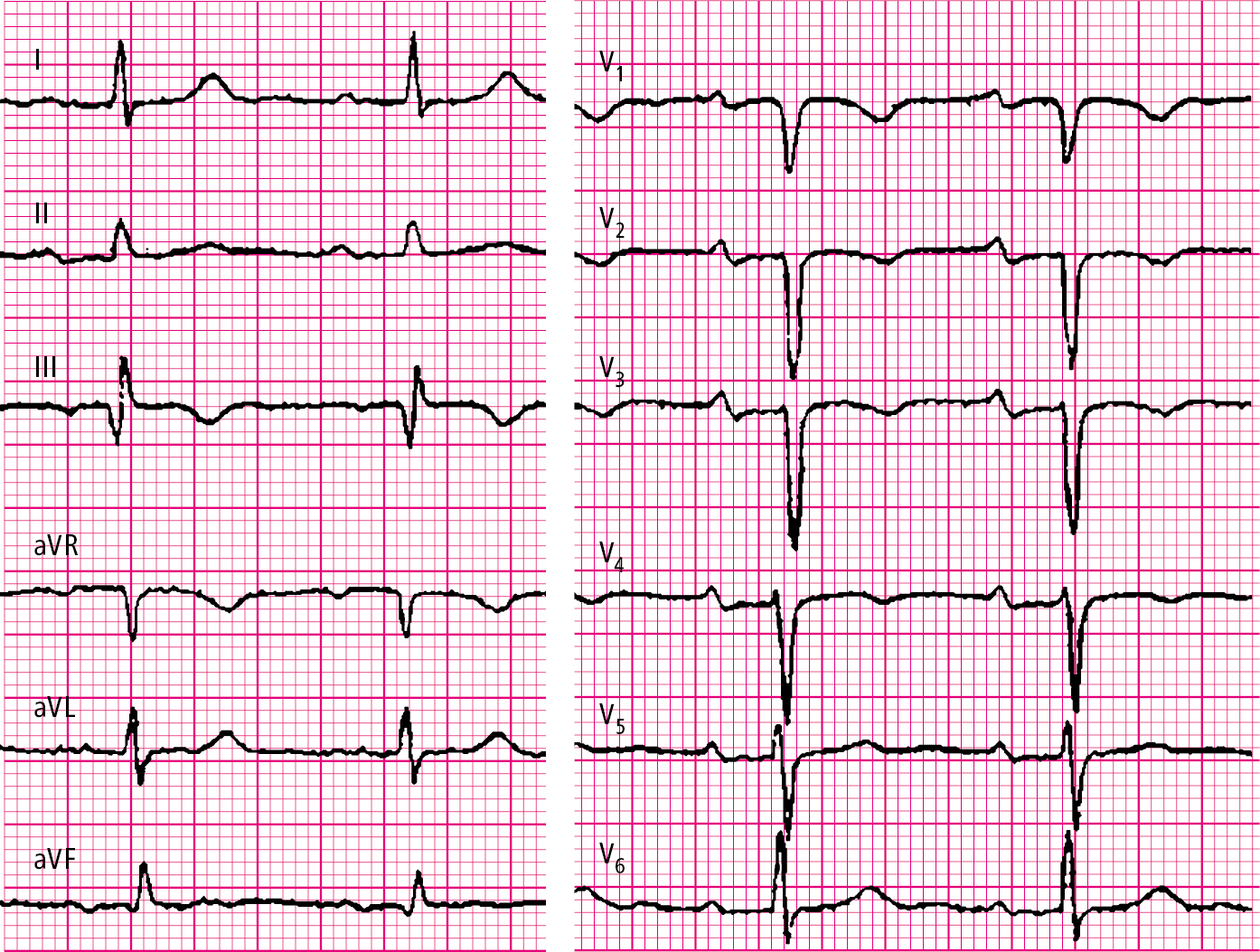

2. Electrocardiography (ECG) (Figure 3.20-1): Tachycardia; supraventricular arrhythmias as well as nonspecific ST-segment and T-wave changes (typically inverted T waves in leads III and V1-V2) may also occur. Rare features include SIQIIITIII syndrome, right axis deviation, and incomplete or complete right bundle branch block. In patients with PE causing hemodynamic instability, negative T waves in leads V2 to V4 and sometimes up to lead V6 are often observed.

3. Chest radiography may reveal enlargement of the cardiac silhouette, pleural effusion, elevated hemidiaphragm, dilation of the pulmonary artery or its rapid cutoff, paucity of the blood vessels on the affected side, atelectasis, and parenchymal opacification.

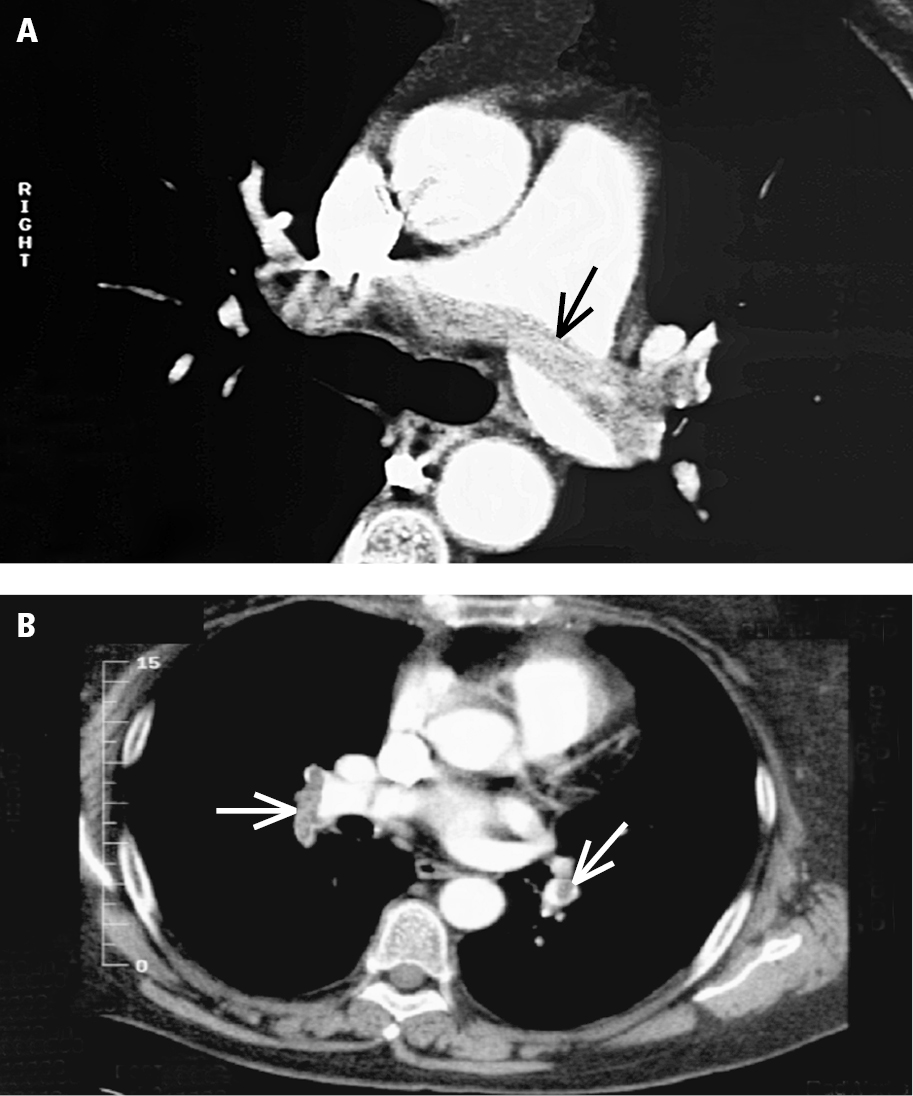

4. Computed tomography angiography (CTA) (Figure 3.20-2) allows for accurate assessment of the pulmonary arteries from the pulmonary trunk to the segmental arteries. Multislice CT (MSCT) also includes the subsegmental arteries (the clinical significance of isolated thrombi in these arteries is controversial). Additionally, CTA reveals interstitial pulmonary lesions.

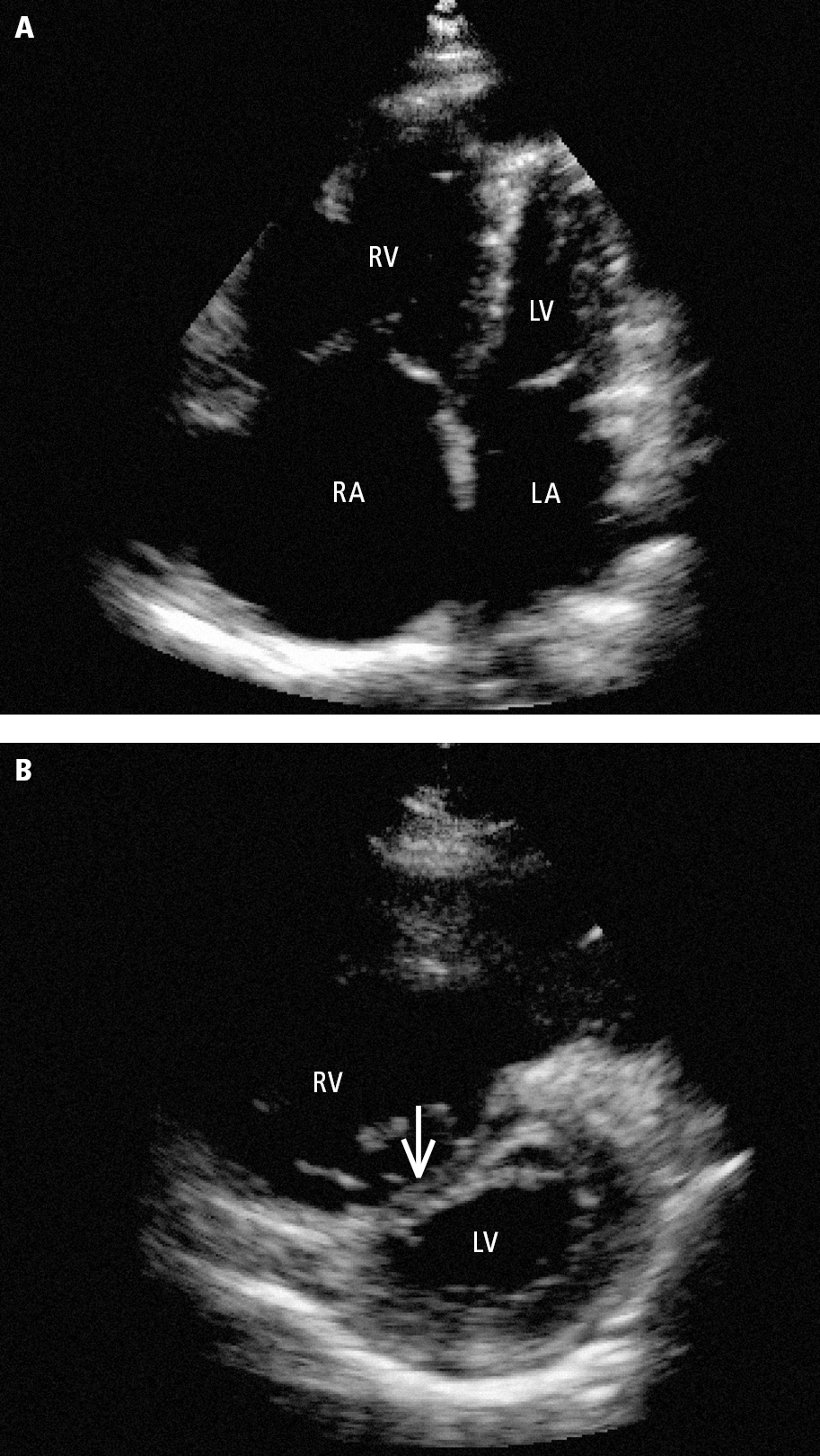

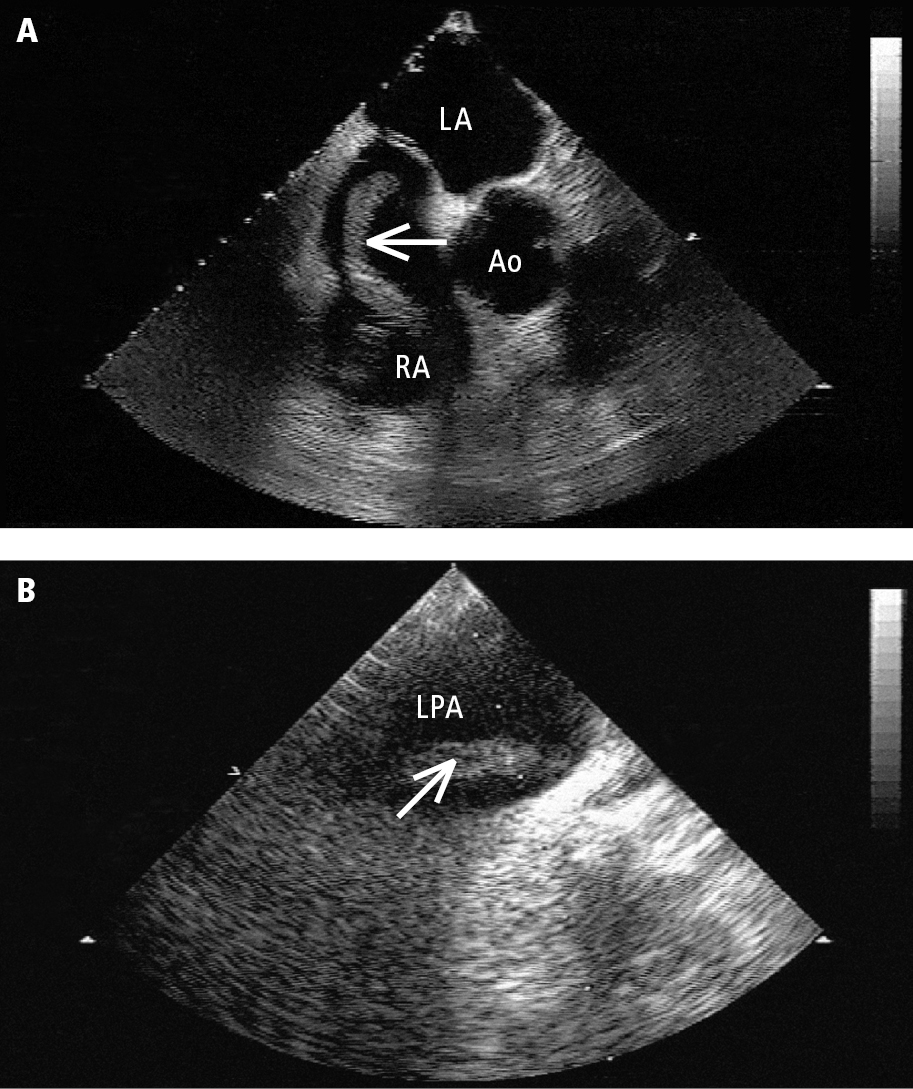

5. Echocardiography: In patients with high-risk or intermediate-risk PE this may reveal right ventricular dilation and thinning of the interventricular septum (Figure 3.20-3). A characteristic finding is a hypokinetic right ventricular free wall with preserved apical contractility, as well as dilation of the inferior vena cava due to right ventricular failure and right atrial hypertension. Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) allows for the visualization of the pulmonary arteries up to the proximal parts of the lobar arteries and thus detects emboli more effectively than transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) (Figure 3.20-4).

6. Ultrasonography of the deep veins of the lower extremities: Compression ultrasonography (CUS) and/or ultrasonography of the entire venous system of the limb may reveal thrombosis.

7. Other studies: Pulmonary ventilation-perfusion (V/Q) scintigraphy is performed less often because of its limited availability and the advantages of CTA. However, V/Q scintigraphy provides less radiation exposure than CTA and is the first-line test during pregnancy. It should be considered in women of child-bearing age or other patients who do not have concomitant lung pathology, which can lead to indeterminate test results. Pulmonary angiography is used rarely because of its invasiveness.

A patient with suspected PE requires a rapid diagnostic workup. The management strategy depends on the patient’s condition and availability of diagnostic studies.

1. Evaluate the risk of early death:

1) High-risk PE: Symptoms of shock or hypotension (systolic blood pressure [SBP] <90 mm Hg or SBP fall by ≥40 mm Hg lasting >15 minutes, if not caused by arrhythmia, hypovolemia, or sepsis).

2) Non–high-risk PE: No manifestations of shock or hypotension.

a) Intermediate-risk PE: Features of right ventricular dysfunction (observed on echocardiography or CTA; elevated BNP/NT-proBNP levels) or positive markers of myocardial damage (increased levels of troponin T or I). The risk is additionally increased if the features of right ventricular dysfunction and myocardial damage occur simultaneously.

b) Low-risk PE: Absence of the above-mentioned features of right ventricular dysfunction and markers of myocardial damage.

2. Evaluate the clinical probability of PE (eg, using the Wells score [Table 3.20-13] or the modified Geneva score [Table 3.20-14]) in a patient with non–high-risk PE. In patients with suspected high-risk PE, the clinical probability of PE is usually high. Diagnostic tests can also be used to consider an alternative diagnosis (eg, ECG may be used to assess for acute coronary syndrome or acute pericarditis and chest radiography may be used to assess for pneumonia or pneumothorax). The exclusion of alternative diagnoses can increase the clinical probability for PE, which requires specific diagnostic testing.

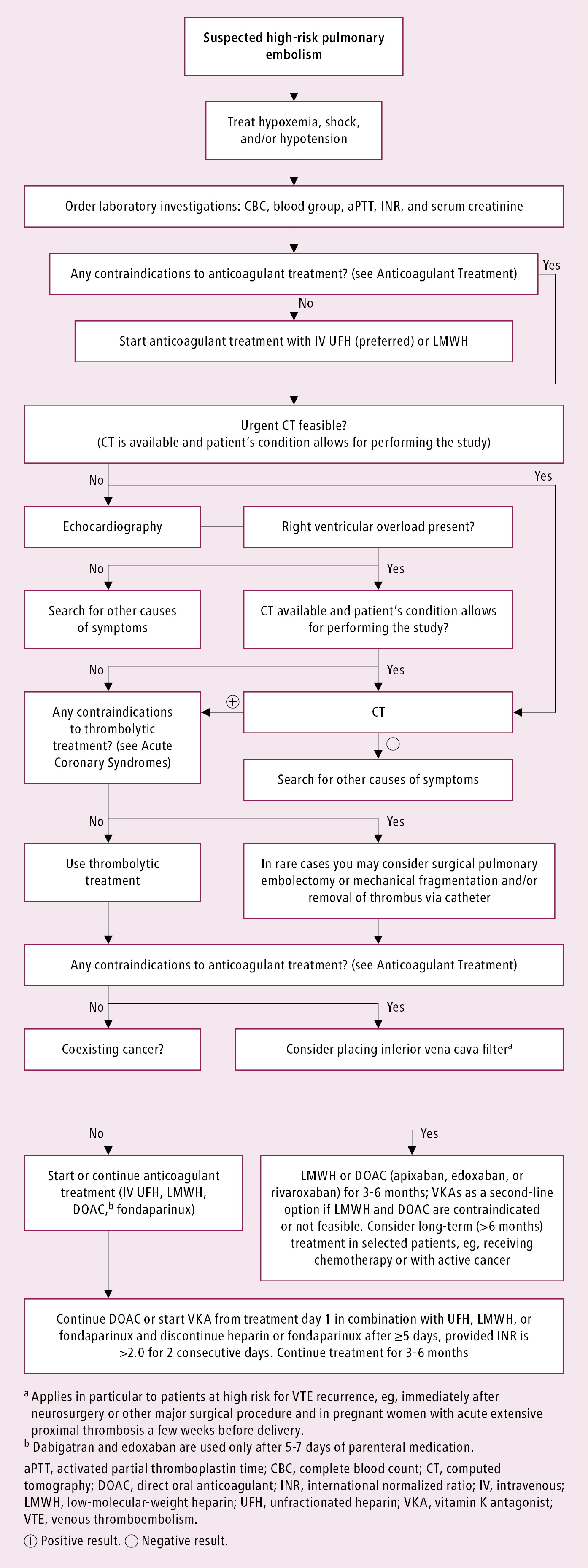

3. Diagnostic tests in patients at high risk with suspected PE: Figure 3.20-5. To confirm the diagnosis, perform urgent CTA or a V/Q lung scan. If this is unavailable, or if CTA cannot be performed due to the patient’s condition, bedside echocardiography may be helpful in providing indirect evidence for PE (eg, dilated right ventricle, increased pulmonary artery pressure).

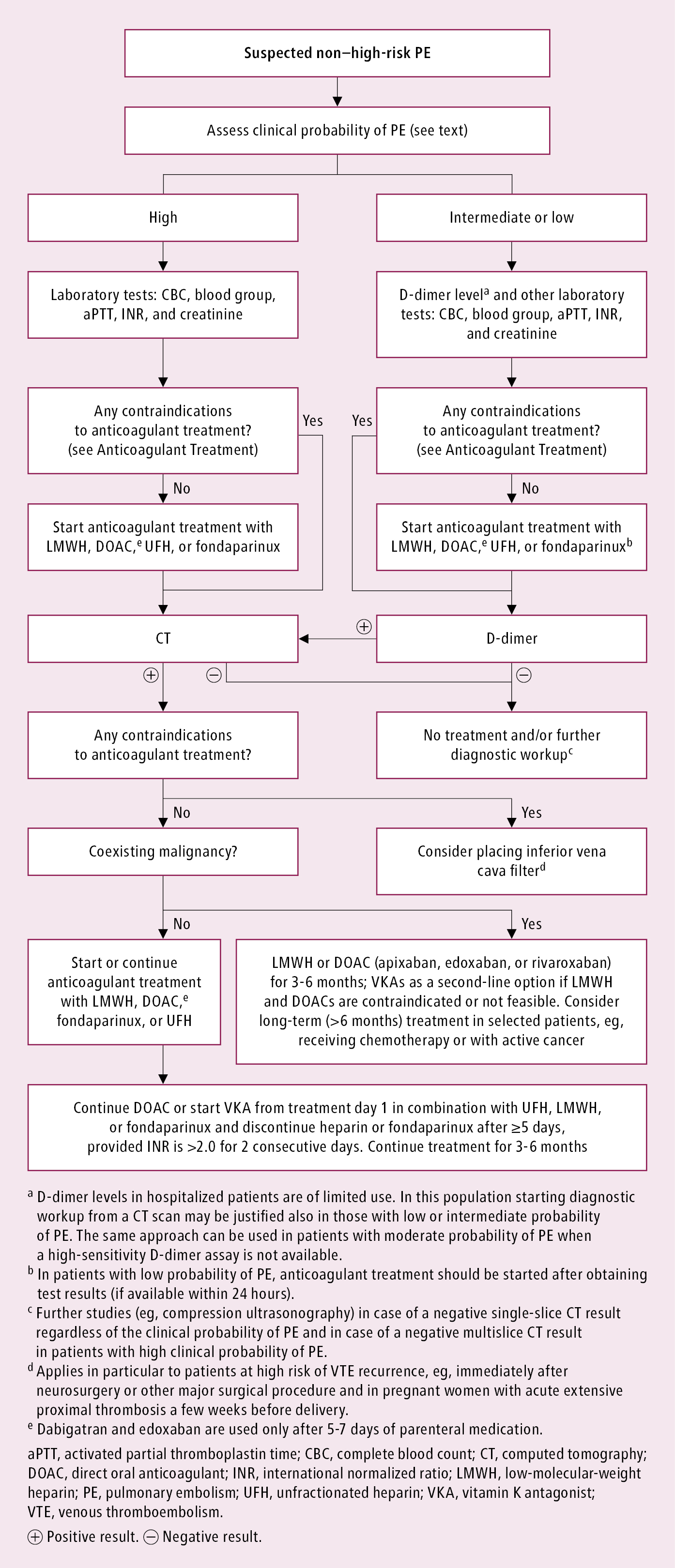

4. Diagnostic tests in patients not at high risk with suspected PE: Figure 3.20-6.

1) Patients with a low clinical probability of PE: Measure the D-dimer level using a high-sensitivity (~95%) or moderate-sensitivity (~85%) assay. A normal D-dimer level is sufficient to exclude PE and further investigations and treatment are not necessary. If the D-dimer level is elevated, perform CTA. A negative CTA result excludes PE and allows for the safe discontinuation of anticoagulant treatment.

2) Patients with an intermediate clinical probability of PE: Measure the D-dimer level using a high-sensitivity (~95%) assay. A normal D-dimer level is sufficient to exclude PE and further investigations and treatment are not necessary. If the D-dimer level is elevated, perform CTA. A negative CTA result excludes PE and allows for the safe discontinuation of anticoagulant treatment.

3) Patients with a high clinical probability of PE: Measurement of D-dimer levels is not recommended and CTA should be performed. In patients with an indeterminate CTA result, consider a V/Q scan or bilateral CUS to assess for DVT.

The diagnosis of PE in non–high-risk patients is confirmed by a thrombus observed in CTA and extending to the level of segmental arteries. If embolism is limited to a single subsegmental artery and there is no evidence of thrombosis elsewhere (eg, lower limb DVT), anticoagulant therapy may not be warranted.

There are two ways that a modified D-dimer testing approach may be considered, to decrease the need for diagnostic imaging (with CTA or V/Q scan). The first is age-adjusted D-dimer testing, which appears to increase the specificity of D-dimer without decreasing its sensitivity. In patients aged >50 years, a D-dimer test is considered negative if the result is less than the patient’s age × 10 (eg, D-dimer is negative in an 80-year-old if the test result <800 ng/mL). For patients <50 years, a D-dimer level <500 microg/L remains the cutoff point for a negative result. The second is adjusting the D-dimer threshold for a positive test according to pretest probability. If a high-sensitivity D-dimer assay is used, the combination of a Wells score ≤4 and D-dimer <1000 ng/mL can identify patients with a low likelihood of PE who do not require additional diagnostic testing.

5. Diagnosis of PE in pregnancy: The measurement of D-dimer levels is of limited value because they may be elevated due to pregnancy, particularly in the second half of pregnancy. If the D-dimer is negative, there is insufficient evidence that it can be used to exclude DVT without further diagnostic imaging. The initial diagnostic test is lower extremity venous ultrasonography, because the diagnosis of DVT is sufficient to start anticoagulant therapy without further diagnostic testing for PE. Diagnostic tests involving ionizing radiation should only be performed in pregnant women with normal bilateral lower limb venous ultrasonography. A V/Q scan and CTA can be done during pregnancy, but V/Q scanning is suggested as an initial test because it has been better studied and there is more radiation exposure to the mother with CTA.

Pneumonia and pleurisy, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), pneumothorax, acute respiratory distress syndrome, HF, acute coronary syndrome (eg, in the case of ST-T changes in a patient with chest pain), intercostal neuralgia and other causes of chest pain; and in the case of high-risk PE, also cardiogenic shock, cardiac tamponade, and aortic dissection.

Severe HF and exacerbation of COPD are risk factors for VTE and may coexist with PE.

TreatmentTop

Treatment of high-risk PE: Figure 3.20-5.

1. Start symptomatic treatment:

1) Treat hypotension/shock as in patients with right ventricular failure (see Acute Heart Failure). Note that intensive fluid resuscitation may have harmful effects due to an increase in right ventricular overload.

2) Depending on the presence and severity of respiratory failure, administer oxygen and consider indications for mechanical ventilation.

2. IV unfractionated heparin (UFH): Administer UFH immediately at a loading dose of 80 IU/kg (up to 5000 IU) as an IV bolus provided that anticoagulant treatment is not contraindicated (see Heparins). This is followed by a continuous IV infusion at the rate of 18 IU/kg/h (or up to 1300 IU/h). Assess the activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) after 6 hours. If the aPTT value is within the therapeutic range (1.5-fold to 2.5-fold prolongation compared with the reference value; usually aPTT in the course of treatment should be 60-90 seconds), continue the infusion at the same dose (the average maintenance dose is 25,000-35,000 IU/d); otherwise increase or decrease the dose of UFH accordingly (see Table 3.20-3).

3. Thrombolytic therapy: Thrombolytic therapy is suggested in patients with clinically massive PE, defined as anatomically moderate to large PE associated with persistent systemic hypotension (SBP <90 mm Hg). Thrombolytic therapy should be considered only in patients without contraindications to treatment, although most are relative contraindications in the setting of life-threatening PEEvidence 1Weak recommendation (benefits likely outweigh downsides, but the balance is close or uncertain; an alternative course of action may be better for some patients). Moderate Quality of Evidence (moderate confidence that we know true effects of the intervention). Quality of Evidence lowered due to imprecision. Kearon C, Akl EA, Ornelas J, et al. Antithrombotic Therapy for VTE Disease: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. Chest. 2016 Feb;149(2):315-352. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2015.11.026. Epub 2016 Jan 7. Erratum in: Chest. 2016 Oct;150(4):988. PMID: 26867832. (see ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction (STEMI)). Early confirmation of PE using imaging studies is indicated, but in critically ill patients the decision to use thrombolysis can be made solely on the basis of the clinical features suggestive of PE. In some patients bedside cardiac echocardiography may provide indirect evidence to support a diagnosis of massive PE (right ventricular dilation, elevated pulmonary artery pressure, paradoxical septal motion).

Thrombolytic therapy can be administered systemically, with dose regimens shown below, or by a catheter-directed method through an indwelling catheter placed in the pulmonary artery near the clot.

For systemic administration of thrombolytic therapy, the following drug regimens can be used:

1) Streptokinase:

a) Accelerated regimen (preferred): 1.5 million IU administered IV over 2 hours.

b) Standard regimen: 250,000 IU administered IV over 30 minutes followed by 100,000 IU/h.

2) Recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rtPA) (alteplase):

a) Standard regimen: 100 mg IV over 2 hours.

b) Accelerated regimen: 0.6 mg/kg (maximum, 50 mg) over 15 minutes.

3) Tenecteplase (TNK): 30 to 50 mg (depending on weight) as a bolus over 5 to 10 seconds.

In patients who were previously receiving IV heparin and now require thrombolytic therapy, typically in the setting of clinical deterioration despite heparin therapy, it is safe to immediately administer thrombolytic therapy after stopping heparin. After a streptokinase or rtPA infusion IV heparin can be resumed without a loading dose (bolus).

In patients with cardiac arrest the immediate administration of 50 mg of IV alteplase (injected over 1 minute) and starting cardiopulmonary resuscitation may be life saving. Thrombolytic therapy is most effective when administered within 48 hours of the onset of PE symptoms, but it may have beneficial effects even after 6 to 14 days.

Catheter-directed thrombolysis, although not directly compared with systemic thrombolysis in randomized trials, can be considered as a means to develop a smaller overall dose of thrombolytic drug (eg, rtPA, 1 mg/h infusion) in close proximity to a thrombus with the aim of limiting the systemic thrombolytic effect. This approach can be considered especially in patients who are at high risk for bleeding, for example, those with recent surgery (within 2 weeks).

4. If the patient has not received heparin prior to the administration of the thrombolytic agent, administer IV UFH 80 IU/kg (up to 5000 IU) and then start a continuous infusion of UFH at a rate of 18 IU/kg/h (up to 1300 IU/h) while monitoring aPTT. If a loading dose of UFH has been used before the thrombolytic agent, you may continue UFH infusion together with infusion of the thrombolytic agent or start UFH after discontinuation of the agent. Evidence is lacking regarding whether UFH should be continued during the concurrent administration of thrombolytic therapy; it is suggested that UFH not be coadministered during thrombolytic therapy.

5. Once thrombolytic therapy has been discontinued, with the patient stabilized while still receiving heparin, start long-term anticoagulation with a VKA or a direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) following the same principles as in DVT (see Deep Vein Thrombosis).

6. In the case of contraindications to anticoagulant treatment in patients at high risk of PE recurrence, that is, with extensive proximal DVT, consider placement of an inferior vena cava filter. The filter is inserted via the femoral vein or the internal jugular vein and placed in the inferior vena cava, below the ostia of the renal veins. This treatment is sometimes also indicated in selected patients with severe pulmonary hypertension (to protect against even a minor PE episode, which in this situation could be life threatening) or after pulmonary embolectomy. If the risk of bleeding has decreased, start anticoagulant treatment and remove the filter. Do not place the inferior vena cava filter while patients are receiving anticoagulant treatment.

7. If thrombolytic therapy is contraindicated or ineffective (hypotension or shock persists), as well as in the case of a mobile thrombus in the right ventricle or right atrium (particularly passing through the foramen ovale), consider pulmonary embolectomy (surgical removal of the thrombus from the pulmonary arteries, performed using extracorporeal circulation). In the case of a thrombus located proximally in the pulmonary arteries, consider percutaneous embolectomy or fragmentation of the thrombus using a catheter. Such interventions should only be considered in specialized centers with experienced operators.

1. In all patients with suspected PE start anticoagulant treatment while still waiting to perform diagnostic tests if the results cannot be obtained within 12 to 24 hours. In patients with a high or intermediate clinical probability of PE start anticoagulant treatment immediately, without waiting for the results of diagnostic tests.

2. Anticoagulant treatment regimen: see Deep Vein Thrombosis.

Treatment of Intermediate-Risk PE

Treatment is the same as in patients with low-risk PE, but in patients with right ventricular overload and myocardial dysfunction it should be started in a clinical setting with continuous monitoring of heart rate and blood pressure. In case of clinical deterioration, start “rescue” thrombolytic treatment, and if this is contraindicated, perform embolectomy or percutaneous intervention, depending on the clinical setting and availability.

1. Non–high-risk PE: see Deep Vein Thrombosis.

2. High-risk PE: If this is life-threatening for the pregnant patient, consider thrombolytic therapy (it may cause bleeding into the placenta and lead to miscarriage). Pulmonary embolectomy is also associated with a high risk for both the child and the mother.

3. Do not use DOACs in pregnancy.

Treatment of PE in Patients with Obesity

With the worldwide rise in the prevalence of obesity, there is a corresponding increase in the need to manage patients with obesity who develop PE.

1. Initial drug treatment (first 3 months):

1) Low-molecular-weight heparins (LMWHs) can be used with a weight-adjusted treatment regimen for patients with a body mass index (BMI) ≤40 kg/m2 or body weight ≤120 kg (eg, enoxaparin 120 mg bid or dalteparin 12,000 IU bid). For patients with a BMI >40 kg/m2 or weighing >120 kg, the dose of LMWH is empiric but may consist of a capped or weight-adjusted dose.

2) DOACs can be used in patients with a BMI ≤40 kg/m2 or body weight ≤120 kg, with standard DOAC dosing regimens as in patients without obesity.

3) VKAs are an acceptable option for patients with obesity, following the initial 5 to 7 days of LMWH, administered to achieve an international normalized ratio (INR) target of 2.5 (range, 2.0-3.0) as in patients without obesity.

4) For patients with DVT and a BMI >40 kg/m2 or body weight >120 kg, anticoagulant management is empiric and should be done in consultation with a hematologist or thrombosis specialist.

2. Long-term treatment (after the initial 3 months): DOACs or VKAs are acceptable options for long-term treatment, administered as in patients without obesity.

See Deep Vein Thrombosis. While continuing treatment with heparin, consider switching from UFH to LMWH or fondaparinux.

PreventionTop

1. See Primary Prevention of Venous Thromboembolism.

2. Prevention of recurrent VTE: see Deep Vein Thrombosis.

Tables and FiguresTop

|

Parameter |

Score (original) |

Score (simplified) |

|

|

Predisposing factors |

|||

|

History of DVT or PE |

1.5 |

1 |

|

|

Recent surgery or immobilization |

1.5 |

1 |

|

|

Cancer |

1 |

1 |

|

|

Symptoms: Hemoptysis |

1 |

1 |

|

|

Signs |

|||

|

Heart rate >100 beats/min |

1.5 |

1 |

|

|

Signs and symptoms of DVT |

3 |

1 |

|

|

Clinical assessment: Alternative diagnosis less likely than PE |

3 |

1 |

|

|

Interpretation |

|||

|

Clinical probability (3 levels; original score) Low clinical probability: total score 0-1 Intermediate clinical probability: total score 2-6 High clinical probability: total score ≥7 Clinical probability (2 levels; original score) PE not likely: total score 0-4 PE likely: total score >4 Clinical probability (2 levels; simplified score) PE not likely: total score 0-1 PE likely: total score ≥2 |

|||

|

Adapted from Thromb Haemost. 2000;83(3):416-20 and Thromb Haemost. 2008;99(1):229-34. |

|||

|

DVT, deep vein thrombosis; PE, pulmonary embolism. |

|||

|

Parameter |

Score (original) |

Score (simplified) |

|

|

Predisposing factors |

|||

|

Age >65 years |

1 |

1 |

|

|

Previous deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism |

3 |

1 |

|

|

Surgery or fracture in the past month |

2 |

1 |

|

|

Active malignant condition |

2 |

1 |

|

|

Symptoms |

|||

|

Unilateral lower limb pain |

3 |

1 |

|

|

Hemoptysis |

2 |

1 |

|

|

Signs |

|||

|

Heart rate 75-94 beats/min |

3 |

1 |

|

|

Heart rate ≥95 beats/min |

5 |

2 |

|

|

Pain on deep venous palpation of the lower limb and unilateral edema |

4 |

1 |

|

|

Interpretation |

|||

|

Clinical probability (3 levels; original score) Low clinical probability: total score 0-3 Intermediate clinical probability: total score 4-10 High clinical probability: total score ≥11 Clinical probability (3 levels; simplified score) Low clinical probability: total score 0-1 points Intermediate clinical probability: total score 2-4 points High clinical probability: total score ≥5 points Clinical probability (2 levels; original score) Pulmonary embolism unlikely: total score 0-5 points Pulmonary embolism likely: total score ≥6 points Clinical probability (2 levels; simplified score) Pulmonary embolism unlikely: total score 0-2 points Pulmonary embolism likely: total score ≥3 points |

|||

|

Adapted from Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(19):2131-6 and Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(3):165-71. |

|||

Figure 3.20-1. Electrocardiography (ECG) of a patient with intermediate-risk pulmonary embolism: SIQIII syndrome, inverted T waves in right precordial leads V1 through V4; PR interval prolonged to 220 milliseconds.

Figure 3.20-2. Computed tomography angiography (CTA) of pulmonary embolism: A, a saddle embolus (arrow); B, emboli in peripheral branches (arrows).

Figure 3.20-3. Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) of right ventricular overload in a patient with pulmonary embolism: A, an enlarged right ventricle dominating the left ventricle seen in the apical 4-chamber view; B, flattened interventricular septum (arrow) seen in the parasternal short-axis view. LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; RA, right atrium RV; right ventricle.

Figure 3.20-4. Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE): A, a mobile thrombus (arrow) in the right atrium (RA); B, a thrombus (arrow) in the left pulmonary artery (LPA). Ao, aorta; LA, left atrium.

Figure 3.20-5. Management algorithm in patients with high-risk pulmonary embolism.

Figure 3.20-6. Management algorithm in patients with non–high-risk pulmonary embolism.