This transcript was revised on June 8, 2020, to provide additional commentary on the use of corticosteroids.

Internal Medicine Rapid Refreshers is a series of concise information-packed videos refreshing your knowledge on key medical issues that general practitioners may encounter in their daily practice. This episode reviews the essential points to remember when approaching community-acquired pneumonia.

Contents

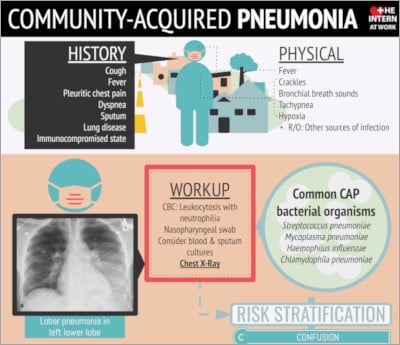

Infographic

Click to view the full image.

Infographic courtesy of The Intern at Work (theinternatwork.com).

Useful links

- Chapter on community-acquired pneumonia from the McMaster Textbook of Internal Medicine

- Chapter on computed tomography in COVID-19 from the McMaster Textbook of Internal Medicine

- Podcast on pneumonia from The Intern at Work

- CURB-65 score at mdcalc.com

- PSI/PORT score at mdcalc.com

- 2016 practice guidelines for hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated pneumonia by the American Thoracic Society (ATS) and Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA)

- 2019 practice guidelines for community-acquired pneumonia by the ATS and IDSA

Transcript

Introduction

I’m Heather Bannerman, a senior medical resident from McMaster University. In this video we will go through a practical approach to pneumonia. This Rapid Refresher is intended for physicians who are returning to general internal medicine during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. This is not meant to serve as medical advice to the general population.

Remember that you do not have to manage patients alone. There are many physicians in the hospital that you can call for additional assistance.

Overview

Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) is defined as an acute infection of the pulmonary parenchyma in a patient who has acquired the infection in the community, as distinguished from hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP). CAP is a common and potentially serious illness associated with considerable morbidity and mortality, particularly in older adult patients and those with significant comorbidities.

There are many potential organisms that can cause pneumonia. We will cover the most common ones. When considering causes of pneumonia, it is important to think about the patient’s place of residence, history of previous infections, recent antibiotic use or hospitalization, and underlying comorbidities. Frequent bacterial causes of CAP:

- Streptococcus pneumoniae

- Haemophilus influenzae

- Mycoplasma pneumoniae

- Chlamydia pneumoniae

- Staphylococcus aureus

- Moraxella catarrhalis

- Legionella species

Consider the patient’s risk factors for more resistant organisms such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) or Pseudomonas. These include prior isolation of these pathogens, recent hospitalization, or recent parenteral antibiotics.

Viral causes are also important to consider, including the novel coronavirus:

- Influenza A/B

- Parainfluenza

- Adenovirus

- Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV)

- Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), causing COVID-19

Previous guidelines recommended differentiating CAP from health-care–associated pneumonia (HCAP). The 2019 guidelines from the American Thoracic Society (ATS) and Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) suggest abandoning the term HCAP in favor of physicians covering empirically for MRSA or Pseudomonas if locally validated risk factors for either pathogen are present.

Assessment: History and physical examination

When first assessing a patient, always consider their airway, breathing, and circulation (ABC). Make sure to assess how much oxygen the patient is requiring and if those requirements are increasing.

Look at the patient to see if they are exhibiting any signs of respiratory distress (speaking in short sentences, tripod posture, accessory muscle use, pursed-lip breathing, abdominal breathing). Monitor closely for signs of hemodynamic instability, such as tachycardia, hypotension, or altered mental status.

On history, typical symptoms of pneumonia include fever, pleuritic chest pain, cough (with or without sputum), dyspnea, and effort intolerance. Elderly patients may have more nonspecific symptoms, such as altered mental status. Make sure to ask the patient about any comorbidities, which could worsen their prognosis or cause you to consider an alternative diagnosis.

On physical examination, make sure to complete a full cardiorespiratory examination. Tachypnea, tachycardia, crackles, bronchial breath sounds, dullness to percussion, or evidence of chronic respiratory disease may be present.

Always keep your differential diagnosis in mind when completing the physical examination to ensure other findings are not overlooked:

- Acute coronary syndrome (ACS)

- Congestive heart failure

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) exacerbation

- Pulmonary embolism

- Aspiration pneumonia

- Pneumothorax

Assessment: Investigations

For patients being admitted with a presumptive diagnosis of pneumonia, the following bloodwork (blood testing) should be included: a complete blood count (CBC) with peripheral smear, renal function and liver enzymes (to assess for severity of systemic disease), and troponin (to assess for ACS). An arterial blood gas (ABG) should be ordered to assess for both hypoxemia and hyperventilation or hypoventilation.

Chest radiography (CXR), with posteroanterior (PA) and lateral views if possible, is critical in determining what pattern of radiographic disease might be present. In the case of COVID-19 the literature to date has demonstrated the presence of bilateral opacities with a peripheral predominance [see computed tomography in COVID-19].

A nasopharyngeal swab (NPS) is important for the detection of respiratory viruses, including SARS-CoV-2. Consider blood cultures, especially in more severe cases or patients with a history of resistant pathogens, and a sputum culture if possible, especially in the context of chronic respiratory disease. Obtain an electrocardiogram (ECG) to exclude ACS or to assess for signs of right heart strain in pulmonary embolism (PE). Consider computed tomography pulmonary angiography (CTPA) if the patients has tachycardia, lack of consolidation on CXR, or hemoptysis. A urine Legionella antigen may also be considered in patients with severe CAP.

Management

As always, consider ABCs, intravenous (IV) lines, oxygen, monitors, and the severity of the patient’s illness when deciding where they should be admitted.

There are scores to assess the severity of CAP, such as the CURB-65 score (confusion, urea, respiratory rate, blood pressure, age ≥65 years) and Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI). These scores can help determine inpatient versus outpatient care and are linked above.

If you’ve decided to admit the patient to the hospital, you will need to consider whether they will be admitted to a ward bed, a step-down bed (more highly monitored), or an intensive care unit (ICU) bed.

A patient should be directly admitted to the ICU if they are hypotensive and require vasopressors or they have respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation. A step-down bed is usually appropriate for patients requiring fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) >50%. Remember it is always important to continue to monitor for increasing oxygen requirements or signs of respiratory distress or failure.

For supplemental oxygen therapy, your goal should be an oxygen saturation (SpO2) >92% (88%-92% in patients with underlying COPD and a history of a chronically elevated partial pressure of carbon dioxide).

For antibiotics, the vast majority of patients can be started on a beta-lactam and a macrolide, which should cover most gram-positive, gram-negative, and atypical organisms that are common in CAP. A reasonable starting regimen is ceftriaxone 1 to 2 g IV daily and azithromycin 500 mg IV or orally daily. An alternative regimen is a respiratory fluoroquinolone.

If the patient has risk factors for MRSA, start vancomycin empirically. If the patient has risk factors for Pseudomonas, select an anti-Pseudomonas beta-lactam (eg, ceftazidime or piperacillin/tazobactam [brand name Tazocin]). For patients with suspected aspiration, antibiotic coverage is not always indicated unless moderate to severe disease is present.

If there is a high suspicion for influenza, consider empiric oseltamivir (brand name Tamiflu) 75 mg orally 2 times a day (bid).

Other supportive care interventions include IV fluids depending on volume status, short-acting bronchodilators in case of wheezing on examination or history of underlying COPD, and chest physiotherapy if respiratory secretions are present. No nebulized treatments are recommended, as these are aerosol-generating and should be avoided if possible.

The 2019 ATS/IDSA guidelines recommended not using corticosteroids (CSs) in adults with nonsevere CAP (strong recommendation, high quality of evidence). These guidelines also did not recommend routine use of CSs in adults with severe CAP (conditional recommendation, moderate quality of evidence) nor did they recommend using CSs in adults with severe influenza pneumonia (conditional recommendation, low quality of evidence). However, the guidelines did endorse the Surviving Sepsis Campaign recommendations on the use of CSs in patients with CAP and refractory septic shock.

Antibiotics can be discontinued at 5 days if the patient is clinically stable. This means they have resolution of vital sign abnormalities, the ability to eat, and an intact Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS). Longer therapy (eg, 7-10 days) may be required if the patient does not meet the above criteria for stability or if they have pneumonia secondary to another infection.

Credits

Thank you for watching our Rapid Refresher on CAP. I’d like to thank my consultant author, Doctor Rebecca Amer (Divisions of Respirology and Internal Medicine; consultant for this video), and Doctor Roman Jaeschke (Divisions of Critical Care and Internal Medicine; editor for this video).

If you’d like to look at any of the resources, they are linked above.

English

English

Español

Español

українська

українська